Penguins are on the front line of climate change, as rising global

temperatures melt the ice the iconic and lovable creatures call home. Scientists who count the birds are finding that penguins are beginning

to feel major impacts from the drastic changes to their habitat.

But, perhaps surprisingly, the breeding populations of three

brush-tailed species of penguins inhabiting the Western Antarctic

Peninsula, where the temperatures are warmest, are not all falling as

the ice is quickly melting. "We know two of the three penguin species in the peninsula, chinstrap

and Adélie, are declining significantly in a region where, in the last

60 years, it's warmed by 3 degrees C. (5 degrees F.) annually and by 5

degrees C. (9 degrees F.) in winter," said Ron Naveen, the founder of

Oceanites, a U.S. based non-profit and scientific research organization.

He oversees the Antarctic Site Inventory which monitors penguin

populations.

A third species, however, has not been losing numbers and in fact has even been expanding its range.

Counting penguins

in the wild is a complicated art. Naveen's team makes repeated visits

every year to the Antarctic Peninsula from November to February when

egg-laying and chick creching are at their peak.

Since 1994, he has conducted 1,421 visits to the peninsula and collected data from 209 sites.

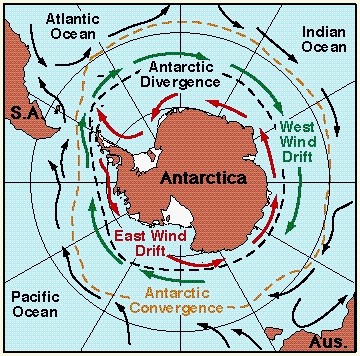

Naveen and fellow penguin counter Heather Lynch of Stony Brook

University say the warming climate and the consequent loss of sea ice

are contributing to the decline in Adelie and chinstrap, because the two

species are dependent on the ice. Warming temperature is only one part of the whole story, however, according to the Naveen. "There are a number of possibilities," he said.

Adelies and chinstrap nest primarily near the ice and rely on krill as

their main food source. These shrimp-like vertebrates live underneath

the ice, feeding on the algae that grows there. As the ice retreats, the

krill disappear.

Other factors such as commercial overfishing and the expanding

population of humpback whales, which also feed on krill, may also

contribute to the loss of their main food source. By contrast, Gentoo penguins, the third of these species, are expanding

both in numbers and in geographical range, according to Naveen and

Lynch's research. There are an estimated 387,000 Gentoo breeding pairs

and their populations are moving southward along the peninsula. "Gentoos are an open water species and can move southward as the

declining ice concentration makes new habitat available to them," Lynch

said.

Gentoos, the most flexible of the three species, will eat anything, not

just krill, and can adjust their life cycle more easily in response to

variable conditions. If the snow melts early, for example, they can

breed earlier or relay their eggs.

Naveen uses simple tools to conduct his field work -- a handheld

counting device known as a tally counter, a pencil, and a notebook --

and combines the data with Lynch's work with remote sensing to ascertain

as complete a count as possible.

Lynch analyzes hi-res satellite images to help her map out and analyze

contours of breeding colonies, look at biological and physical data sets

to determine breeding pairs, and assess breeding populations in remote

places too difficult to get to, such as some locations in the South

Sandwich Islands.

The team's combination of field work and remote sensing allowed them to

get the first site-wide inventory of Penguins at Deception Island. For example, Naveen found 79,849 breeding pairs of chinstrap penguins,

including 50,408 breeding pairs at Baily Head. That 2012 census,

combined with data from Lynch's satellite imagery,

also indicates the chinstrap population has declined 50 percent as

compared to previous population estimates conducted in 1987.

Monitoring penguin populations in the western Antarctic Peninsula, how

they shrink and grow in response to changing conditions, not only

provides critical clues to how to manage the environment down there, but

perhaps for us as well, Naveen said. "Are they sending us a message we should be thinking about?" he said. "Are we canaries in the coal mine?"

No comments:

Post a Comment