Researching species via satellite can be cheaper, easier, and more accurate.

Brown smudges show an emperor penguin colony at Cape Colbeck, Antarctica, in a 2010 satellite image. Satellite photograph courtesy DigitalGlobe, Inc.

Published July 28, 2014

Take Seth Stapleton, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, who published a study this month in PLOS ONE on new ways to spot far-flung polar bears, including leveraging the same satellite that provides images for Google Earth. Even though polar bears are the biggest bear species alive

today and one of the most widely studied large mammals on Earth, we know

surprisingly little about their whereabouts across much of the remote

Arctic.

To find the white bears on the icy landscape, Stapleton and

colleagues restricted their scope to darker islands where bears often

get stranded in the late summer after the surrounding ice melts. The researchers successfully identified nearly a hundred

polar bears by satellite. In a separate test, they verified that what

they were seeing were actually bears (and not rocks or foam) by

conducting aerial surveys in a helicopter.

What's more, new advances in satellite resolution and

automation may one day allow us to count polar bears no matter what

they're standing on. "The technology is evolving so rapidly, it has the potential to open

up huge areas of research and conservation avenues," said Stapleton.

Let's take a look at a few more animals getting the cosmic paparazzi treatment.

Emperor penguins are seen in Dumont d'Urville in

April 2012. Counting emperor penguins in Antarctica wasn't easy until

researchers used new technology to map the birds from space.

Photograph by Stringer, Reuters/Corbis

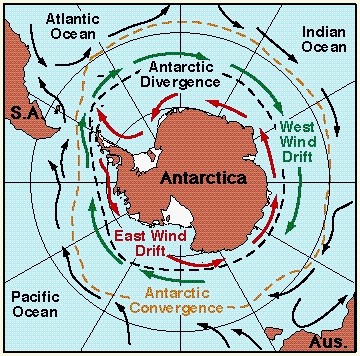

Emperor Penguins

Emperors may be the largest penguins on Earth,

but that isn't the only thing that makes them visible from space. In

fact, the most conspicuous evidence of an emperor penguin colony is what

they leave behind on the ice—their poop. "The brown stains stand out really well on the fresh snow,"

said Peter Fretwell, a scientist with the British Antarctic Survey.

(Related: "Emperor Penguins Counted From Space—A First.")

Using Landsat satellite images of Antarctica, Fretwell and his colleagues have found

that they can use these "fecal stains" as an indicator of a potential

colony. Once the team finds a brown spot, they can zero the satellites

in to count birds individually or make population estimates based on how

many penguins are huddled together.

Just by looking at such satellite images, Fretwell and his

colleagues have more than doubled the number of known emperor penguin

colonies.

Right Whales

Fretwell also led a study about detecting whales from space, published in PLOS ONE in 2013. Instead of scanning the whole ocean for whale tails, or flukes, his study focused on Golfo Nuevo, Argentina—a bay where right whales come to breed between July and November. Breeding areas are ideal for counting whales by satellite

because many species choose calm, clear waters where they can bask near

the surface with their calves.

Fretwell found that it was indeed possible to manually

count whales by satellite. What's more, he and his team looked at

possible ways computer animation could help scientists cover more

ground.

For instance, in the simplest analysis, the researchers

found that the computer could identify all the bright areas of a

whale-ish size and shape on a given image.

In fact, Fretwell said right whales may be easier for a

computer to identify than other species, on account of the gray-white

calluses that grow on the animal's dark heads. Just imagine having a growth on your face visible from space.

Bats, Birds, and Turtles

If the goal is to spot an animal using satellite imagery, then the animal will obviously have to be relatively large. For instance, Stapleton said an adult male polar bear appears as no more than six to eight white pixels using the WorldView-2 satellite. But a new addition to the International Space Station, called ICARUS

(International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space), may one

day soon help scientists keep tabs on individual animals smaller than a Smart car.

Most GPS tags log location data but lack the power to

transmit that information up to a satellite. This means a study animal

must be recaptured at some point to obtain that information—a

particularly difficult feat when you're working with small migratory

animals. But with the new ICARUS hardware, scientists will be able

to employ more advanced GPS tags that transmit information back to the

space station, which orbits much closer to Earth than most satellites

do.

The ICARUS Initiative aims to track birds, bats, sea

turtles, and rodents to better understand ecosystems, improve aviation

safety, track endangered species, and monitor the spread of infectious

diseases. And the transmitters are getting smaller all the time. One day soon, it may be possible to monitor a single monarch butterfly flying in your backyard from more than 200 miles (320 kilometers) up in the sky.

Now that's out of this world.

No comments:

Post a Comment