22 March 2012

Posted by kramsayer

Researchers

have identified the source of a spike of atmospheric acidity over an

Antarctic site - penguin poop. (Credit: Flickr user Chadica, http://bit.ly/GNl1ku)

The Adélie penguins that inhabit the area (think of the wise-cracking group from Happy Feet) produce tons of guano, according to atmospheric scientist Anne-Mathilde Thierry. Literally, their output is about one metric ton (2,205 pounds) per day, explained the Ph.D. student at the Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien in Strasbourg, France, and co-author of a new study revealing the unexpected effect of that pronounced penguin production.

The study will be published next week in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, a publication of the American Geophysical Union.

Previous scientific investigations of the atmosphere over this coastal area, known as Dumont d’Urville, have detected releases of oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs), which cause acidity and which were traced back to natural marine processes in the nearby ocean. However, Michel Legrand of the Laboratoire de Glaciologie et Géophysique de l’Environnement in Grenoble, France, lead author of the new study, and his colleagues found that the compounds, called alkenes, released by the marine processes in December 2010 were insufficient to make up all the OVOCs – and therefore all the acid – present. OVOCs, in general, are easily vaporized chemicals such as acetic acid, acetaldehyde, and acetone. They form through both natural and human-induced processes, including the burning of vegetation, vehicle exhaust, and natural plant emissions, but are short-lived in the atmosphere.

Stumped trying to explain the December OVOC spike, Legrand discussed the puzzle with Thierry. Soon their conversation turned to penguin guano and bacterial activity in the soils that guano eventually becomes. When alkenes released by the decomposing penguin guano were taken into account, the increased levels of acidity made more sense. More alkenes reacting with ozone molecules meant more OVOCs being produced, which would lead to more atmospheric acidity.

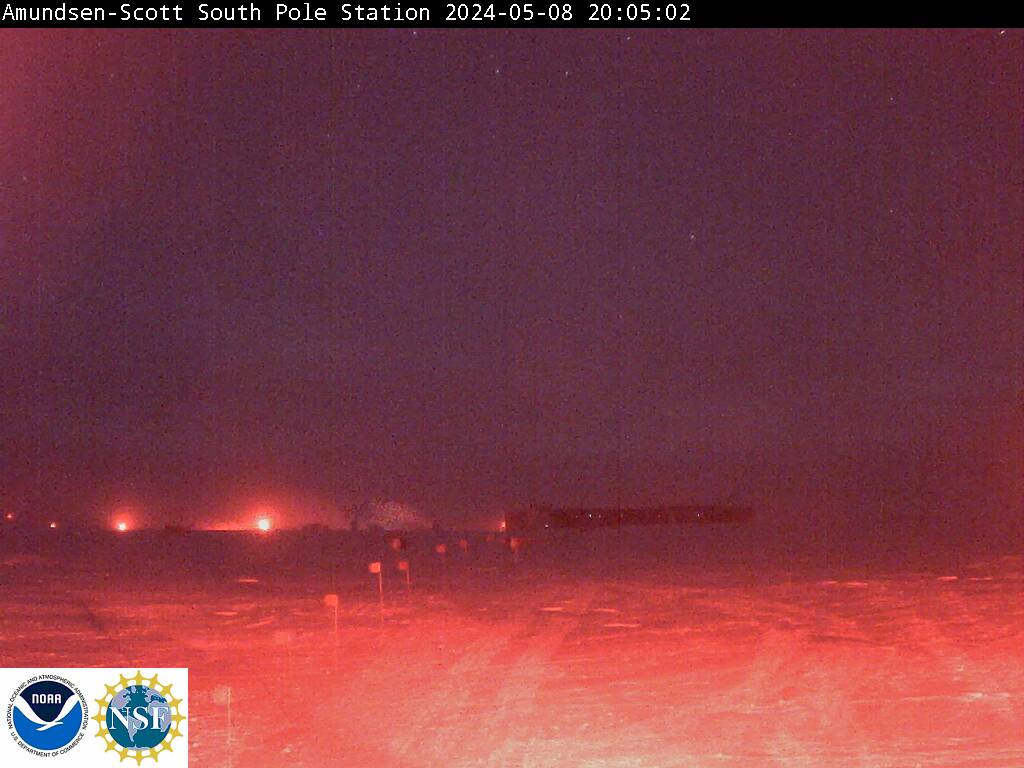

Noting that there had been unusually mild weather in December 2010 that sped up decomposition of guano into alkenes, they “started to consider that penguins could have something to do with the increase in atmospheric acidity,” Thierry explained.

“It had to be the penguins! So we took samples of both fresh and old guano so that the chemists could do some more analyses,” she said.

It turns out getting sample supplies of penguin guano for testing was not too difficult. “When you study penguins, you tend to get guano on your clothes during a typical day of work – so it wasn’t much of a trouble to get the fresh guano samples,” Thierry said.

While the acidity over Dumont d’Urville was remarkable enough to prompt a scientific investigation, it isn’t enough to set off environmental or ecological alarms, Legrand said.

Large amounts of OVOCs can affect the atmosphere’s ability to cleanse itself, but the increased quantities of acids in this case are too small to cause harm. “At the local scale, the high concentrations of acetic acid make this acid dominant compared to other acidic species,” noted Legrand. Yet, “I don’t think the species emitted by penguin colonies have a significant detrimental effect,” he added.

For a break from the science of it, check out Sea World San Diego’s penguin cam.

Legrand, M., Gros, V., Preunkert, S., Sarda-Estève, R., Thierry, A., Pepy, G., & Jourdain, B. (2012). A reassessment of the budget of formic and acetic acids in the boundary layer at Dumont d’Urville (coastal Antarctica): The role of penguin emissions on the budget of several oxygenated volatile organic compounds Journal of Geophysical Research DOI: 10.1029/2011JD017102