by Claire Christian

The way climate change research is reported in the media can be confusing, even if it’s part of your job to keep up with the latest findings. As many, many commentators, scientists, and fake news anchors have noted, this unfortunately means that people think that climate change, if it exists, is some sort of scam cooked up by environmentalists who want to stop doing fun things like removing mountaintops and dumping them into streams so we can get more coal to burn. The truth is that climate change is a complex phenomenon. If you don’t understand this, you are likely to run into trouble when you read news stories about scientific research, sometimes even when those stories are really not about proving or disproving climate change. Take this post, for example. The writer completely misrepresents the results of a recent global Adélie survey by Lynch and LaRueand fans the flames of climate denialism.

The post suggests that this research and other studies indicate that penguins are doing super great under climate change, so why can’t we all stop worrying? In fact, these studies don’t say that at all. We know this because we actually talked to the researchers involved. To clarify a few technical points, the survey by Lynch and LaRue demonstrates that the known breeding population of Adélie penguins is 53% larger than was previously estimated in 1993. As the paper points out, this increase in known breeding population is roughly divided between growth at known populations and the discovery of several new populations, the latter of which include some populations that were so remote that they may have simply been missed in previous surveys. Nevertheless, the survey results do suggest that the populations of breeding Adélie penguins in East Antarctica and in the Ross Sea have grown over the last several decades, and these increases in abundance have more than offset the losses previously reported on the Antarctic Peninsula (and confirmed by this recent study).

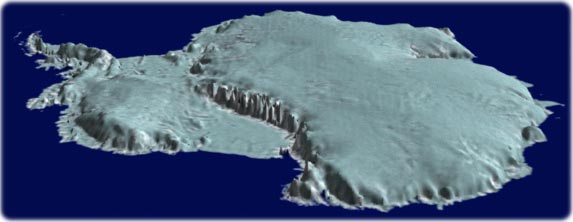

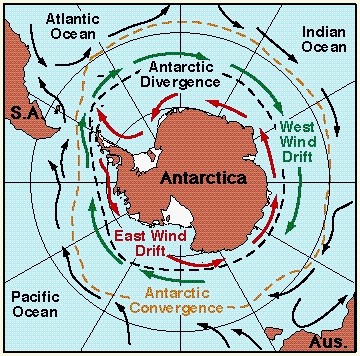

These kinds of results are not particularly surprising to people who follow Antarctic scientific research closely. Antarctica is a big place, and climate change affects different regions of the continent differently. The Antarctic Peninsula is warming more rapidly than other Antarctic areas, and more rapidly than the rest of the world, save, perhaps, for the Arctic. So although the total number of Adélie penguins has not declined, climate change is still having a measurable impact on Antarctica. This may be good for penguins in some areas like East Antarctica and the Ross Sea, but it doesn’t mean that warmer temperatures are necessarily a Good Thing for Adélies, the continent as a whole, or the planet.

In fact, the authors note that one climate-related explanation for increasing populations may be glacial retreat (not happy news if you live in a coastal city), which opens up new habitat for Adélie penguin breeding. Study author Heather Lynch also notes, “That climate change may cause both increases and decreases in Adélie penguin populations is a tribute to its utility as a biomonitor, and highlights the Adélie’s important role as an early warning system for ecological change. Adélie penguin increases have previously been linked to a growing toothfish fishery, which itself presents concerns over the influence of Southern Ocean fisheries on the Antarctic food web.” Therefore, what’s important about this study is that it establishes a “baseline for understanding future changes in abundance and distribution”, not that it proves that all is well with penguins now and forever.

Another penguin researcher (not connected with the global Adélie survey study) who was also quoted in the National Review’s blog post, Ron Naveen, told me that “To suggest that Adélies are booming or that all penguins globally are booming is bad reporting. The only way to really know that, of course, would be to compare the latest numbers with a previous survey using the same technology — and that's not possible. Rather, the big story is that we humans know more than we did because we now have more sophisticated tools in our kit. And, as a result, we have much improved baselines for detecting and assessing change.”

Species-threatening decreases in abundance, such as those projected to occur for emperor penguins within the next century (see Jenouvrier et al.'s recent paper in Nature Climate Change), remain a grave concern. Other rapid changes in abundance and distribution, including the increasing abundance reported by Lynch and LaRue, provide a reminder that both climate change and resource extraction can upset the natural ecological balance of the Southern Ocean. While the warning signs in this case represent good news for the Adélie penguin as a species, they nevertheless reflect major changes in Southern Ocean ecosystems that will have enormous consequences. Thus the Adélie penguin can be both be helped and hurt by climate change. It’s not the kind of simple message the media likes, but it’s a scientific reality.

Claire Christian

Director, Secretariat

Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition

source

The way climate change research is reported in the media can be confusing, even if it’s part of your job to keep up with the latest findings. As many, many commentators, scientists, and fake news anchors have noted, this unfortunately means that people think that climate change, if it exists, is some sort of scam cooked up by environmentalists who want to stop doing fun things like removing mountaintops and dumping them into streams so we can get more coal to burn. The truth is that climate change is a complex phenomenon. If you don’t understand this, you are likely to run into trouble when you read news stories about scientific research, sometimes even when those stories are really not about proving or disproving climate change. Take this post, for example. The writer completely misrepresents the results of a recent global Adélie survey by Lynch and LaRueand fans the flames of climate denialism.

The post suggests that this research and other studies indicate that penguins are doing super great under climate change, so why can’t we all stop worrying? In fact, these studies don’t say that at all. We know this because we actually talked to the researchers involved. To clarify a few technical points, the survey by Lynch and LaRue demonstrates that the known breeding population of Adélie penguins is 53% larger than was previously estimated in 1993. As the paper points out, this increase in known breeding population is roughly divided between growth at known populations and the discovery of several new populations, the latter of which include some populations that were so remote that they may have simply been missed in previous surveys. Nevertheless, the survey results do suggest that the populations of breeding Adélie penguins in East Antarctica and in the Ross Sea have grown over the last several decades, and these increases in abundance have more than offset the losses previously reported on the Antarctic Peninsula (and confirmed by this recent study).

These kinds of results are not particularly surprising to people who follow Antarctic scientific research closely. Antarctica is a big place, and climate change affects different regions of the continent differently. The Antarctic Peninsula is warming more rapidly than other Antarctic areas, and more rapidly than the rest of the world, save, perhaps, for the Arctic. So although the total number of Adélie penguins has not declined, climate change is still having a measurable impact on Antarctica. This may be good for penguins in some areas like East Antarctica and the Ross Sea, but it doesn’t mean that warmer temperatures are necessarily a Good Thing for Adélies, the continent as a whole, or the planet.

In fact, the authors note that one climate-related explanation for increasing populations may be glacial retreat (not happy news if you live in a coastal city), which opens up new habitat for Adélie penguin breeding. Study author Heather Lynch also notes, “That climate change may cause both increases and decreases in Adélie penguin populations is a tribute to its utility as a biomonitor, and highlights the Adélie’s important role as an early warning system for ecological change. Adélie penguin increases have previously been linked to a growing toothfish fishery, which itself presents concerns over the influence of Southern Ocean fisheries on the Antarctic food web.” Therefore, what’s important about this study is that it establishes a “baseline for understanding future changes in abundance and distribution”, not that it proves that all is well with penguins now and forever.

Another penguin researcher (not connected with the global Adélie survey study) who was also quoted in the National Review’s blog post, Ron Naveen, told me that “To suggest that Adélies are booming or that all penguins globally are booming is bad reporting. The only way to really know that, of course, would be to compare the latest numbers with a previous survey using the same technology — and that's not possible. Rather, the big story is that we humans know more than we did because we now have more sophisticated tools in our kit. And, as a result, we have much improved baselines for detecting and assessing change.”

Species-threatening decreases in abundance, such as those projected to occur for emperor penguins within the next century (see Jenouvrier et al.'s recent paper in Nature Climate Change), remain a grave concern. Other rapid changes in abundance and distribution, including the increasing abundance reported by Lynch and LaRue, provide a reminder that both climate change and resource extraction can upset the natural ecological balance of the Southern Ocean. While the warning signs in this case represent good news for the Adélie penguin as a species, they nevertheless reflect major changes in Southern Ocean ecosystems that will have enormous consequences. Thus the Adélie penguin can be both be helped and hurt by climate change. It’s not the kind of simple message the media likes, but it’s a scientific reality.

Claire Christian

Director, Secretariat

Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition

source

No comments:

Post a Comment