A mother

Weddell seal with her pup in front of Mt. Erebus in the Ross Sea,

Antarctica. The tagged mother and pup are both part of MSU's long-term

study of population dynamics in Weddell seals in Erebus Bay, Antarctica.

(Credit: Photo by Jay Rotella, ecology department, Montana State

University)

ScienceDaily (Oct. 3, 2012) —

Montana State University ecologists who are about to return to

Antarctica for another season had to adapt to dramatic changes in the

sea ice last year.

Now they have published a paper that says the Weddell seals they

monitor had to deal with some dramatic changes in ice in recent years,

too. In fact, the seals handled the adverse conditions well and suffered

less than the Emperor penguins in that region.

The paper was published Sept. 26 in the international journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Lead author was Thierry Chambert, a doctoral student supervised by co-authors Bob Garrott and Jay Rotella in the MSU ecology department. Rotella and Garrott have just received a National Science Foundation grant for $867,272 that will extend their long-term study by five more years.

Last year, the researchers encountered unusually thin ice that was three feet thick instead of the usual 12 to 16 feet, Garrott said. Large cracks and active breaks threatened snowmobile travel. As a result, the faculty members and students moved their base camp to a safer spot and set up emergency camps around their study area. When they couldn't cross the ice on snowmobiles, they flew by helicopter.

In the course of their work, Rotella said the researchers saw how the Weddell seals faced their own challenges from massive icebergs that broke off and dramatically changed sea-ice conditions in a number of recent years.

Using data from 29 years, the team was able to compare seal numbers, as well as rates of pup production and adult survival, from before, during, and after the iceberg event, to learn how the seals fared. The number of seals they observed and the number of pups that were born during the peak of the iceberg event were down to unprecedented low numbers, but monitoring showed that, "the seals, in fact, handled the event quite well," Rotella said.

He explained that the seals were able to maintain high survival rates by lowering their breeding efforts during the years of iceberg presence. They tended to avoid breeding colonies when sea-ice conditions were particularly unfavorable.

The Emperor penguins, however, continued their normal activities during the worst of the iceberg event. The result was dramatic with dying penguins, as well as breeding failures, Rotella said. He noted that moving ice crushed eggs and even some adults at the peak of the iceberg event. Exhaustion and starvation might also have been an issue for penguins that walked across the ice from open water to their nesting colonies.

"These results reveal that, depending on their ecology, different species can suffer different impacts from an extreme environmental disturbance," said Rotella, the new leader of the Weddell seal study.

"The results also reveal the importance of having long-term data to evaluate possible effects," Rotella continued. "Without the data, we couldn't have known whether this extreme environmental event had extreme consequences for the seals or not. Fortunately for the seals, it did not. We learned that the seals were quite capable of riding out the massive changes in ice conditions as long as they didn't persist too long."

Rotella said the relationship between thinner ice and icebergs is outside of his field of expertise, but he said that ice provides protection from predators like orcas and leopard seals. It also serves as a platform for Weddell seals in the first few weeks of their lives when they have little fat for staying warm in the water and can't swim well yet. When the ice is thinner, predators have better access to the breeding areas used by penguins and Weddell seals for rearing their young. It is also easier for storms to shatter the ice sheets and for the area to have open water.

No one knows what this season will bring for sea-ice conditions, but the MSU researchers said they hope it isn't a repeat of last year.

"That was very challenging," Garrott said. "We really don't know what the ice conditions are like this year until we get down there."

This year's field season will run from about Oct. 10 to mid-December, with Rotella going down for the first half of the season and Garrott for the second half. Mary Lynn Price, a video journalist who has joined the group for the past two seasons, will be there for three weeks in the middle, with her stay overlapping Rotella's and Garrott's.

Price will again produce a variety of videos and other materials that will be available to the public.

This will be the 45th season for the study that Garrott and Rotella took over around 2001 from Don Siniff at the University of Minnesota. Initiated by Siniff, the study is one of the longer running animal population studies and the longest marine mammal study in the southern hemisphere. It not only focuses on changes in the Weddell seal population, but it yields broader information about the workings of the marine environment. The study incorporates information on sea ice, fish, ecosystem dynamics, climate change, and even the Antarctic toothfish, which is marketed in U.S. restaurants as Chilean sea bass.

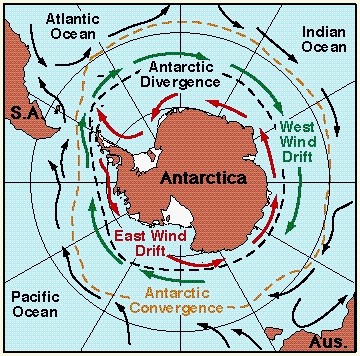

The MSU study concentrates on pups and adult breeding females that live in the Ross Sea, which is the most pristine ocean left in the world and the only marine system whose top predators -- including the Weddell seal -- still flourish.

The researchers start the season by weighing and tagging every pup when it's about two days old. Later in the season, they visit every colony in their study, collecting genetic samples and recording every tag they find. Weddell seals are relatively gentle for being a top predator in the ecosystem, but they can weigh over 1,000 pounds and have a set of teeth like a bear's, Garrott has said in the past.

Story Source:

Journal Reference:

The paper was published Sept. 26 in the international journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Lead author was Thierry Chambert, a doctoral student supervised by co-authors Bob Garrott and Jay Rotella in the MSU ecology department. Rotella and Garrott have just received a National Science Foundation grant for $867,272 that will extend their long-term study by five more years.

Last year, the researchers encountered unusually thin ice that was three feet thick instead of the usual 12 to 16 feet, Garrott said. Large cracks and active breaks threatened snowmobile travel. As a result, the faculty members and students moved their base camp to a safer spot and set up emergency camps around their study area. When they couldn't cross the ice on snowmobiles, they flew by helicopter.

In the course of their work, Rotella said the researchers saw how the Weddell seals faced their own challenges from massive icebergs that broke off and dramatically changed sea-ice conditions in a number of recent years.

Using data from 29 years, the team was able to compare seal numbers, as well as rates of pup production and adult survival, from before, during, and after the iceberg event, to learn how the seals fared. The number of seals they observed and the number of pups that were born during the peak of the iceberg event were down to unprecedented low numbers, but monitoring showed that, "the seals, in fact, handled the event quite well," Rotella said.

He explained that the seals were able to maintain high survival rates by lowering their breeding efforts during the years of iceberg presence. They tended to avoid breeding colonies when sea-ice conditions were particularly unfavorable.

The Emperor penguins, however, continued their normal activities during the worst of the iceberg event. The result was dramatic with dying penguins, as well as breeding failures, Rotella said. He noted that moving ice crushed eggs and even some adults at the peak of the iceberg event. Exhaustion and starvation might also have been an issue for penguins that walked across the ice from open water to their nesting colonies.

"These results reveal that, depending on their ecology, different species can suffer different impacts from an extreme environmental disturbance," said Rotella, the new leader of the Weddell seal study.

"The results also reveal the importance of having long-term data to evaluate possible effects," Rotella continued. "Without the data, we couldn't have known whether this extreme environmental event had extreme consequences for the seals or not. Fortunately for the seals, it did not. We learned that the seals were quite capable of riding out the massive changes in ice conditions as long as they didn't persist too long."

Rotella said the relationship between thinner ice and icebergs is outside of his field of expertise, but he said that ice provides protection from predators like orcas and leopard seals. It also serves as a platform for Weddell seals in the first few weeks of their lives when they have little fat for staying warm in the water and can't swim well yet. When the ice is thinner, predators have better access to the breeding areas used by penguins and Weddell seals for rearing their young. It is also easier for storms to shatter the ice sheets and for the area to have open water.

No one knows what this season will bring for sea-ice conditions, but the MSU researchers said they hope it isn't a repeat of last year.

"That was very challenging," Garrott said. "We really don't know what the ice conditions are like this year until we get down there."

This year's field season will run from about Oct. 10 to mid-December, with Rotella going down for the first half of the season and Garrott for the second half. Mary Lynn Price, a video journalist who has joined the group for the past two seasons, will be there for three weeks in the middle, with her stay overlapping Rotella's and Garrott's.

Price will again produce a variety of videos and other materials that will be available to the public.

This will be the 45th season for the study that Garrott and Rotella took over around 2001 from Don Siniff at the University of Minnesota. Initiated by Siniff, the study is one of the longer running animal population studies and the longest marine mammal study in the southern hemisphere. It not only focuses on changes in the Weddell seal population, but it yields broader information about the workings of the marine environment. The study incorporates information on sea ice, fish, ecosystem dynamics, climate change, and even the Antarctic toothfish, which is marketed in U.S. restaurants as Chilean sea bass.

The MSU study concentrates on pups and adult breeding females that live in the Ross Sea, which is the most pristine ocean left in the world and the only marine system whose top predators -- including the Weddell seal -- still flourish.

The researchers start the season by weighing and tagging every pup when it's about two days old. Later in the season, they visit every colony in their study, collecting genetic samples and recording every tag they find. Weddell seals are relatively gentle for being a top predator in the ecosystem, but they can weigh over 1,000 pounds and have a set of teeth like a bear's, Garrott has said in the past.

Story Source:

The above story is reprinted from materials provided by Montana State University.

Note: Materials may be edited for content and length. For further information, please contact the source cited above.

Journal Reference:

- T. Chambert, J. J. Rotella, R. A. Garrott. Environmental extremes versus ecological extremes: impact of a massive iceberg on the population dynamics of a high-level Antarctic marine predator. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2012; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1733

No comments:

Post a Comment