Embedded with scientists

New book chronicles four polar research expeditions

Posted January 27, 2012

But Linder is not a scientist per se, though he earned a master’s degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program

He recently published a book about four of his adventures to the Arctic and Antarctic in a book called Science on Ice

The four chapters of the book focus on a particular expedition, each written by a different science journalist. The first chapter features researcher David Ainley

Linder recently answered a few questions from The Antarctic Sun

1. Science on Ice features four research expeditions that you accompanied, along with a science writer, as part of a grant from the National Science Foundation for the International Polar Year

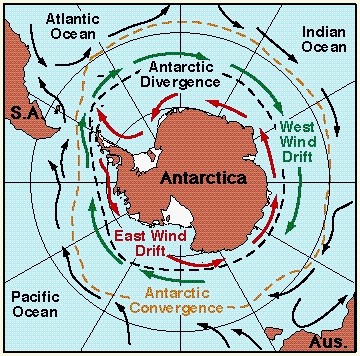

I chose those four particular expeditions to showcase the broad diversity of environments (Ross Island, the Greenland Ice Sheet, Bering Sea, Arctic Ocean) and disciplines (biology, engineering, glaciology, geology, chemistry, physics) that encompass polar science. On our trip to McMurdo Station, we chose to highlight David Ainley’s penguin science research

Having a science background gives me a distinct advantage when photographing fieldwork. I understand how long it takes to get a grant funded and how precious every second of field time is on an expedition. I carefully research each expedition’s logistics and science goals so that I know exactly what is going to happen, when, and why. I never ask scientists to change their activities to suit my images. Instead, I make sure that I am always ready for the action, even if that means working all night or waiting hours to document a unique science event. The science team appreciates my hands-off approach. This makes them more comfortable around the camera, and it’s easier for me to capture candid, behind-the-scenes moments.

3. Since 2002, you have photographed two dozen science expeditions, including 14 to the polar regions, no doubt working closely with many of the researchers you’ve photographed. What have you learned about the world of science by embedding yourself with your subjects for what can be weeks at a time? I know from my experiences that I’ve always been impressed with their commitment and tireless work ethic.

The scientists I photograph are my heroes. Aside from their determination and drive, the other quality that stands out to me is their creativity. Whether it’s dealing with logistical snafus, a broken instrument, or weather delays, researchers always come up with creative solutions to unexpected problems in the field.

4. Aside from the book, you did a number of outreach activities as part of the IPY grant. Would you talk about some of the creative ways you communicated polar research to the public?

One of the most enriching, but stressful, things we did on the Live from the Poles

5. You received a second grant from the NSF in 2010 under its Antarctic Artists and Writers Program

On my first visit to Cape Royds and Cape Crozier, I was amazed by the teamwork and intelligence the skuas displayed as they robbed Adélie penguins of their eggs and chicks. After I returned home, I picked up a copy of Euan Young’s book Skua and Penguin: Predator and Prey, which explains in detail the research done on this topic. Surprisingly (to me), their observations revealed that the skuas acted more like scavengers than predators — essentially, they were eating the eggs and chicks that wouldn’t have survived anyway. I decided to write an Artists and Writers proposal to photograph the life history and behavior of the skuas at Cape Crozier, Ross Island. I spent six weeks photographing the birds, and was lucky enough to witness a wide range of behavior, including a penguin disturbing a skua nest and a skua pair feeding their chick. The story was shot as a first-look agreement with National Geographic magazine, and is still pending publication.

6. Anything you’d like to add?

Photographing these expeditions, with all of the stress,

sleepless nights, and cold fingers, has been the hardest but most

exhilarating job of my life. But the polar bears and penguins don’t make

my job extraordinary; the people do. The scientists who kindly invited

me to join their expeditions, the crews of the ships and field camps who

kept me alive and happy, and the readers of the Polar Discovery website source

No comments:

Post a Comment