The big picture

Posted February 17, 2012

Colonies of ice-dependent Adélie penguins along the western side of the peninsula are blinking out of existence. A subantarctic species called gentoos that disdain ice is thriving, pushing farther south. The third species of brushtail penguin known as the chinstrap is somewhere in the middle.

All of this is under way in a region considered one of the fastest warming in the world. It’s where average year-round temperatures are 3 degrees Celsius higher over the last 60-plus years — and about double that during just the winter season.

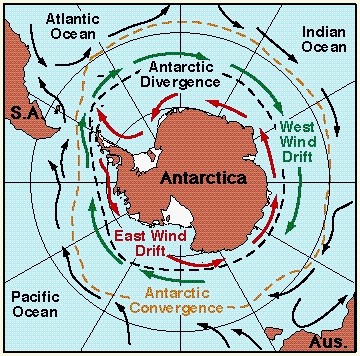

A driving force in the success and failure of the different penguins revolves around sea ice, its extent and duration shrinking dramatically in recent decades. Such a scenario means that the true Antarctic penguin, the Adélie, is losing habitat to the subantarctic gentoos and chinstraps.

That’s the story. But it’s not the whole picture, according to scientists who have recently published a paper in the journal Ecology that synthesized penguin census data from a 31-year period at 70 sites around the Antarctic Peninsula.

The findings suggest that site-specific long-term studies may not accurately reflect regional trends because population responses to climate change vary spatially. By looking at a large number of populations along the Antarctic Peninsula, the authors find that they call the “classic sea ice hypothesis,” while likely still a factor in the dynamics of the food web, “misses many of the key details that emerge from a more comprehensive regional-scale analysis.”

Photo Credit: Jon Brack/Antarctic Photo Library

Adélie penguins at Torgersen Island, Antarctic Peninsula.

More than five years ago, while a post-doctoral fellow with William Fagan

Naveen had the data. Lynch and Fagan had the analytical tools to create models that would pinpoint trends over time and space. For the Ecology paper, the researchers also drew upon other long-term datasets, including those by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The analysis found that Adélies were in significant decline. No surprise there. Out of 24 breeding sites, Adélies were down at 18 sites and increasing significantly at only three colonies. But chinstraps — contrary to some previous research that implied they were mostly thriving alongside gentoos, as both species are not dependent on sea-ice like their cousin — are also failing. The 29 chinstrap sites surveyed found significant declines at 16 sites and increases at seven.

“If you look at the big picture, chinstraps are declining rapidly and regionally,” Lynch said, even more so than Adélies in the last decade.

But none of the changes affecting chinstraps or Adélies appear to be directly related to sea ice, according to the research. That finding supports a paper published last year by NOAA scientists in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We suggest that sea ice no longer drives trends in penguin populations through direct, physical effects on habitat. Rather, sea ice is one of several factors that mediate prey availability to penguins,” wrote the authors, led by Wayne Trivelpiece

The work by Lynch, Naveen and their colleagues also suggest a correlation to food, at least for the peninsula Adélies, which rely almost exclusively on shrimplike krill. They used chlorophyll a as a proxy, or as a way to estimate biological activity, because actual estimates of krill biomass in the Southern Ocean are unavailable on the scales covered by the research.

Chlorophyll a is a green pigment in phytoplankton, microscopic plantlike organisms that float in the ocean. Krill feed on phytoplankton, hence the connection. Scientists believe the little crustaceans are also reliant on sea ice as both a habitat and source of food, as juvenile krill feed on algae that grow under the ice. So sea ice is still in the equation.

The scientists found that neither chlorophyll a nor changes in spring sea ice were correlated to the spatial pattern of chinstrap population declines.

In contrast to the other two Pygoscelis species, gentoo penguin populations are significantly increasing at 32 of 45 sites and significantly decreasing at only nine sites, the researchers reported. Lynch and colleagues found that gentoo colonies are restricted to areas with less than 50 percent sea ice cover in November. Their southward march has been rapid, thanks to the decline in sea ice at that time of year.

“I think we have to rethink the paradigm of population change in all three species,” said Lynch, now an assistant professor at Stony Brook University

Naveen said the disparate findings suggest that researchers still have much to learn about what is driving the ecosystem.

“We want to try to understand more precisely why we’re seeing different responses by these three species in what is a vastly warming ecosystem. It could be food related. It could be oceanography. It could be something else,” he said.

Both scientists made separate expeditions to the Antarctic Peninsula this season, the 18th of the Antarctic Site Inventory, which now includes 142 sites. The current research is partly funded by the NSF’s Office of Polar Programs

Most of Oceanites’ fieldwork is opportunity-based, hitching rides aboard tourist vessels during the Antarctic summer. This year, Naveen and his team were able to raise additional funds and charter the yacht Pelagic. They spent 12 days at Deception Island, home to world’s largest chinstrap colony at a location called Baily Head.

“Deception Island has never been counted like that in one season, let alone in a 12-day period. We’re pretty excited about the results,” Naveen said.

The manuscript describing their findings is still in the works, but Lynch said the numbers will shock those scientists familiar with the Baily Head colony.

“We have found a complete collapse of the penguin colony there,” she said. “I was there this year, and it’s like a ghost town.”

Meanwhile, this season Lynch worked aboard the research vessel Laurence M. Gould

“We spend a lot of time chasing ghosts and going to a lot of empty colonies now,” she said.

Photo Credit: ©Thomas Mueller

A sound recorder installed by the Oceanites/Antarctic Site Inventory team at Baily Head, Deception Island.

“There’s some natural wobble every year when the peak of egg laying occurs. The better and better we get at understanding that date and refining our data, we reduce the error in our analyses,” Naveen explained.

A second device was set up at another location on Cuverville Island, with a large gentoo population. “It’s just another tool that we have in the arsenal. We’ll be testing it out over the next few years to see if it is useful to us, and we’re optimistic,” Naveen said.

Another very useful tool has been high-resolution satellite imagery. Lynch and Naveen predict the technology will eventually lend itself to monitoring penguin colonies around the entire Antarctic. [See related article — Eyes in the sky: Scientists use satellites to track health of seal, penguin populations in Antarctica.]

For instance, counts from satellite pictures matched up closely with previous Oceanites estimates for the Adélie population breeding on Paulet Island in the Weddell Sea, and a more recent analysis shows a near perfect match between satellite image-based estimates and ground counts for chinstraps breeding at Baily Head.

“We’re very clear now that for some of these large colonies, this is the way to go to measure change, to see if the colonies are expanding or shrinking,” Naveen said. “The satellite stuff is going to be pretty amazing.”

Predictions about what might happen to the penguins of the Antarctic Peninsula are a little harder to come by. The current population trends will likely continue, assuming the region’s climate and ecosystem trends also follow their current trajectories.

Regional extinction may be a possibility, unless the penguins can change their behavior. Naveen noted that previous studies of tissue samples of eggs from ancient penguin colonies in the Antarctic Peninsula region show that Adélies once ate a diet similar to gentoos, one more rich in fish.

Human pressures through whaling 200 years ago removed a major predator from the peninsula ecosystem for decades, presumably creating a surplus of krill. Now the whale populations are bouncing back, and krill are fished commercially for products like omega-3 nutrition supplements. Throw in climate change, and there appears to be less krill to go around.

A switch to a less krill-centric diet may help. But a research cruise in 2010 in search of silverfish, a sardine-sized fish favored by penguins, found little evidence that they were still available around the peninsula region — another possible casualty of climate warming. [See previous article — Fishy business: Climate change may be to blame for disappearance of Antarctic silverfish.]

Naveen sees a lesson here: Can species adapt quick enough to a multitude of changes driven by climate change?

“We’re going to see more and more of that around the globe. What’s happening in the peninsula may be giving us some clues as to what we who live in more temperate climates may be facing in the future,” he said.

NSF-funded research in this article: Ron Naveen, Oceanites Inc., Award No. 0739430

source

No comments:

Post a Comment