Posted on September 15, 2012 by Bob Berwyn

Steep drops in chinstrap, Adélie penguin populations linked with global warming, decline of krill

FRISCO — Chinstrap penguin populations around Antarctica — including a major colony at Baily Head on Deception Island — are dwindling, and some have even blinked out in what scientists are calling colony collapse.

But tourism is not a big factor in the decline, according to researchers who compared penguin population trends at heavily visited sites with other spots that aren’t on the Antarctic tourism circuit.

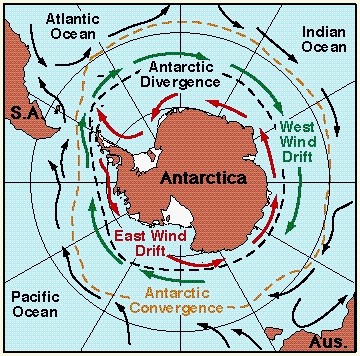

Adélie penguin populations are also dropping regionally. Both species are offshore foragers, so loss of sea ice and changes in krill populations — driven by global warming — are suspected be the primary causes. The Antarctic Peninsula, including the South Shetland archipelago, is warming faster than almost any other part of the planet.

It’s also possible that rebounding humpback whale populations, as well as commercial fishing, are affecting krill distribution to some degrees, but researchers haven’t yet been able to pinpoint those impacts accurately.

New study

In one of the most recent penguin studies, ecologist Heather Lynch, of Stony Brook University, teamed up with other researchers to make a detailed count of breeding chinstrap penguins at Deception Island, including the colony at Baily Head. The scientists worked from a private yacht (not a US research vessel) chartered with grant money from the Tinker Foundation to count nests and also used satellite images for their census.

Comparing the numbers with earlier surveys done in the 1980s, the scientists estimated that the number of breeding chinstrap penguins at Baily Head has dropped by 50 percent since the 1980s, and by as much as 39 percent just in the past seven years.

“For people that have been going down there for decades, it takes their breath away to see how few there are … they say it’s like a ghost town,” Lynch said. “The evidence for a significant decline is very strong. It didn’t surprise anybody … people could see these changes happening, but it was mostly from anecdotal reports.”

It’s difficult to quantify historic chinstrap penguin populations before the 1980s, but the trend from the past 25 years, coinciding with rapid warming in the region, is clear, she said.

“We now know that two of the three predominant penguin species in the Peninsula — chinstrap and Adélie — are declining significantly in a region where, in the last 60 years, it’s warmed by 5 degrees annually and by 9 degrees in winter, said Ron Naveen, founder of the nonprofit science and conservation organization, Oceanites, Inc. “By contrast, gentoo penguins, the third of these species, are expanding both its numbers and range. These divergent responses are an ongoing focus of our inventory work effort,” Naveen said.

Managing tourism

The results of the study should help inform decisions about tourism management at Baily Head and other locations, where previous discussions within the framework of the Antarctic Treaty proceeded without detailed information about penguin population trends.

Deception Island and Baily Head are among the most popular stops for visitors to Antarctica. Last year, about 1,500 tourists visited the chinstrap colony. Because the observed decline in chinstrap penguin numbers coincided with increases in visitation, there was speculation that tourism was impacting the penguins.

But surveys at other sites that are only rarely, or never, visited by tourists showed similar declines. Essentially, the researchers said their study showed no link between tourism and chinstrap penguin population declines.

“We wanted to make sure the Antarctic community didn’t get distracted by tourism and put the focus back on climate change, which seems to be the real issue here,” Lynch said.

There are other concerns related to Antarctic tourism, including a push toward more camping, the continued threat of invasive species, as as the issue of ship collisions and groundings, but at least for now, it appears that visitors aren’t contributing to the decline of the ice-loving sea birds.

Establishing solid baseline data on the penguin populations will also help researchers going forward as they try to determine the exact causes of the decline.

Counting krill

“People have been thinking about Adélies for a long time … they thought chinstrap penguins would benefit, that open-water species would do better,” Lynch said, describing the feeding habits of the various species and explaining that some of the existing models that relied solely on sea ice metrics may not encompass all the possible factors.

“Chinstraps don’t like to forage in sea ice, but they like to eat krill … the thinking is, there’s just not enough krill left to support the populations, but krill are amazingly difficult to survey.”

The decline in sea ice may be hampering the ability of krill populations to recruit new generations, she explained.

“In the juvenile stage of krill, they feed on algae on the underside of ice … that’s what allows them to recruit. It’s this incredibly important bottleneck for them to be able to feed on the underside of the sea ice,” she said, adding that krill populations tend to grow in pulses during “boom years.”

“The concern is, you have to have at least one boom in the life cycle of krill, but the booms are becoming less frequent. There are bigger gaps between years with heavy sea ice,” she said.

The bottom line is that there’s less food available for foraging penguins around the Antarctic Peninsula.

Lynch said she’s a member of an international working group established to try and determine if commercial krill fishing is also a factor.

“We just don’t know yet. Spatially-resolved data on fishing effort are not widely available,” she said.

Based on the fact that the two offshore-foraging species — chinstrap and Adélies — are declining, while gentoo penguins, which forage close to shore are increasing, there’s also a hypothesis that the comeback of humpback whales may be linked with the decline in krill populations, she concluded.

source

1 comment:

thanks

Post a Comment