Systematics

Updated after Marples (1962), Acosta Hospitaleche (2004), and Ksepka et al. (2006). See the gallery for images of most living species.

ORDER SPHENISCIFORMES

- Basal and unresolved taxa (all fossil)

- Waimanu - basal (Middle-Late Paleocene): Waimanu was a genus of early penguin which lived soon after the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event, lending support to the theory that the radiation of modern birds took place before the extinction of the dinosaurs, not after as others had proposed. While it was a very early member of the sphenisciformes, Waimanu was flightless (like all modern members of its order). Though its wing bones do not show the extreme specializations modern penguins have for an aquatic lifestyle, it does seem adapted for wing-propelled diving, and may have resembled a flightless loon. Discovered in Canterbury, New Zealand riverbed sediments (near the Waipara River) of the Waipara Greensand Formation in 1980, the name Waimanu comes from Māori for "waterbird". Two species are known, W. manneringi from the Early Paleocene and W. tuatahi from the Late Paleocene.

- Perudyptes (Middle Eocene of Atacama Desert, Peru) - basal?

- Sphenisciformes gen. et sp. indet. CADIC P 21 (Leticia Middle Eocene of Punta Torcida, Argentina: Clarke et al. 2003)

- Delphinornis (Middle/Late Eocene ?- Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica) - Palaeeudyptinae, basal, new subfamily 1?

- Archaeospheniscus (Middle/Late Eocene - Late Oligocene) - Palaeeudyptinae? New subfamily 2? : Archaeospheniscus is an extinct genus of large penguins. It currently contains three species, known from somewhat fragmentary remains. A. wimani, the smallest species (about the size of a Gentoo Penguin), was found in Middle or Late Eocene strata (34-50 MYA) of the La Meseta Formation on Seymour Island, Antarctica, whereas the other two, about the size of a modern, Emperor Penguin are known from bones recovered from the Late Oligocene Kokoamu Greensand Formation (27-28 MYA) at Duntroon, New Zealand. The genus is one of the earliest known primitive penguins. Its humerus is still very slender, between the form seen in ordinary bird wings and the thickened condition found in modern penguins. On the other hand, the tarsometatarsus shows a peculiar mix of characters found in modern and primitive forms. Whether this signifies that the genus is an ancestor of modern taxa or represents a case of parallel evolution is unknown.

- Species

- Lowe's Penguin (Archaeospheniscus lowei) : Lowe's Penguin (Archaeospheniscus lowei) is the type species of the extinct penguin genus Archaeospheniscus. It stood approximately 85-115 cm high, between a modern King Penguin and an Emperor Penguin in size. It is known from bones of a single individual (Otago Museum C.47.20) and possibly some additional material such as the OM C.47.27 femur, all recovered from the Late Oligocene Kokoamu Greensand Formation (27-28 MYA) at Duntroon, New Zealand. The species' binomen was given in honor of Percy Lowe, who researched prehistoric penguins and proposed a theory (now considered erroneous) that these birds were derived from reptiles independently of the other modern birds.

- Lopdell's Penguin (Archaeospheniscus lopdelli) : Lopdell's Penguin (Archaeospheniscus lopdelli) was the largest species of the extinct penguin genus Archaeospheniscus, standing about 90-120 cm high, or somewhat less than the extant Emperor Penguin. It is only known from bones of a single individual (Otago Museum C.47.21) which was found in the Late Oligocene Kokoamu Greensand Formation (27-28 MYA) at Duntroon, New Zealand. Bones apparently belonging to this species are now also known from the Late Eocene La Meseta Formation (34-37 MYA) on Seymour Island, Antarctica (Tambussi et al., 2006). As the bird is not very well distinguished except in size from its contemporary congener Archaeospheniscus lowei and the size range, an estimated 85-120 cm, is in the upper range of the variation found in modern penguins, it is probable that A. lopdelli is a synonym of A. lowelli. As the recent finds in Antarctica suggest, this is far from certain, however, and there remains much to be learned about the systematics and biogeography of the two larger Archaeospheniscus species. The species' binomen honors J. C. Lopdell, who assisted Marples in recovering the fossils of this bird and others found in the Duntroon excavations.

- Archaeospheniscus wimani : Archaeospheniscus wimani is an extinct species of penguin. It was the smallest species of the genus Archaeospheniscus, being approximately 75-85 cm high, or about the size of a Gentoo Penguin. It is also the oldest known species of its genus, as its remains were found in Middle or Late Eocene strata (34-50 MYA) of the La Meseta Formation on Seymour Island, Antarctica. It is known from a fair number of bones. The species' binomen honors Carl Wiman, an early 20th century researcher who laid the groundwork for the classification of the prehistoric penguins.

- Species

- Marambiornis (Late Eocene -? Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica) - Palaeeudyptinae, basal, new subfamily 1?

- Mesetaornis (Late Eocene -? Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica) - Palaeeudyptinae, basal, new subfamily 1?

- Tonniornis (Late Eocene -? Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica)

- Wimanornis (Late Eocene -? Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica)

- Duntroonornis (Late Oligocene of Otago, New Zealand) - possibly Spheniscinae

- Korora (Late Oligocene of S Canterbury, New Zealand)

- Platydyptes (Late Oligocene of New Zealand) - possibly not monophyletic; Palaeeudyptinae, Paraptenodytinae or new subfamily?

- Spheniscidae gen. et sp. indet (Late Oligocene/Early Miocene of Hakataramea, New Zealand)

- Madrynornis (Puerto Madryn Late Miocene of Argentina) - possibly Spheniscinae

- Pseudaptenodytes (Late Miocene/Early Pliocene) : The extinct penguin genus Pseudaptenodytes contains the type species P. macraei; smaller bones have been assigned to P. minor, although it is not certain whether they are really from a different species or simply of younger individuals; both taxa are known by an insufficient selection of bones. The fossils of Pseudaptenodytes have been found in deposits in Victoria (Australia) which are of Late Miocene or Early Pliocene age.

- Dege (Early Pliocene of South Africa) - possibly Spheniscinae

- Marplesornis (Early Pliocene) - possibly Spheniscinae

- Nucleornis (Early Pliocene of Duinfontain, South Africa) - possibly Spheniscinae

- Inguza (Late Pliocene) - probably Spheniscinae; formerly Spheniscus predemersus : Inguza predemersus is an extinct species of penguin. It was formerly placed in the genus Spheniscus and presumed to be a close relative of the African Penguin, but after its well-distinct tarsometatarsus was found, it was moved into its present monotypic genus. What is known from molecular data is that the time at which the present species lived is not too distant from the arrival of the ancestors of the African Penguin on the Atlantic coasts of southern Africa. On the other hand, it may be closer to Pygoscelis. This would mean that its ancestors diverged from those of the extant Pygoscelis most likely at an indeterminate point of time during the Oligocene.(Baker et al. 2006) Alternatively, it might not be close to extant penguins (the Spheniscinae), but a late survivor of an extant lineage. This is not very likely given its age - it would be the last known survivor of the non-spheniscine penguins - but as some of these still lived a few million years ago, it cannot be ruled out.

- Family Spheniscidae

- Subfamily Palaeeudyptinae - Giant penguins (fossil) : The New Zealand Giant Penguins, Palaeeudyptinae, are an extinct subfamily of penguins. It includes several genera of medium-sized to very large species - including Palaeeudyptes marplesi and Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi which grew 1.5 meters (4 ft 11.1 in) tall or even larger, and the massive Pachydyptes ponderosus which weighed at least as much as an adult human male. They belonged to an evolutionary lineage more primitive than modern penguins. In some taxa at least, the wing, while already having lost the avian feathering, had not yet transformed into the semi-rigid flipper found in modern penguin species: While the ulna and the radius were already flattened to increase propelling capacity, the elbow and wrist joints still retained a higher degree of flexibility than the more rigidly lockable structure found in modern genera. The decline and eventual disappearance of this subfamily seems to be connected by increased competition as mammal groups such as cetaceans and pinnipeds became better-adapted to a marine lifestyle in the Oligocene and Miocene. The members of this subfamily are known from fossils found in New Zealand, Antarctica, and possibly Australia, dating from the Middle or Late Eocene to the Late Oligocene; the Australian Middle Miocene genus Anthropodyptes is also often assigned to this subfamily, as are the remaining genera of primitive penguins except those from Patagonia. Indeed, it was long assumed that all prehistoric penguins which cannot be assigned to extant genera belonged into the Palaeeudyptinae; this view is generally considered obsolete today. It is likely that some of the unassigned New Zealand/ Antarctican/ Australian genera like Delphinornis, Marambiornis, and Mesetaornis do indeed belong into this subfamily, but it is just as probable that others, such as Duntroonornis and Korora, represent another, smaller and possibly somewhat more advanced lineage. The Palaeeudyptinae as originally defined (Simpson, 1946) contained only the namesake genus, the remainder being placed in the Anthropornithidae. The arrangement followed here is based on the review of Marples (1962) who synonymized the two, with updates to incorporate more current findings.

- Crossvallia (Cross Valley Late Paleocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica) - tentatively assigned to this subfamily

- Anthropornis (Middle Eocene ?- Early Oligocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica) - tentatively assigned to this subfamily

- Nordenskjoeld's Giant Penguin, Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi : Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi, or Nordenskjoeld's Giant Penguin, was a penguin species that lived 45–37 million years ago, during the Late Eocene and the earliest part of the Oligocene. It reached 1.7 meters (5 ft 6.9 in) in height and 90 kilograms (198 lb) in weight. Fossils of it have been found on Seymour Island off the coast of Antarctica and in New Zealand. By comparison, the largest modern penguin species, the Emperor Penguin, is just 1.2 meters (3 ft 11.2 in) tall. Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi had a bent joint in the wing; this indicates a carryover from its flying ancestors. Penguins were descended from grebe or loon-like ancestors, and became flightless as they became full-time swimmers.

- Icadyptes (Late Eocene of Atacama Desert, Peru) : Icadyptes salasi was a giant penguin species from the late Eocene period, in the tropics of South America. "Ica" for the Peruvian region where it was found, "dyptes" from the Greek word for diver, and "salasi" for Rodolfo Salas, a noted Peruvian paleontologist. The fossilised remains of the penguin, which lived some 36 million years ago, were found in the coastal desert of Peru by the team of North Carolina State University palaeontologist Dr. Julia Clarke, assistant professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences. Its well-preserved fossil skeleton was found on the southern coast of Peru together with an early Eocene species Perudyptes devriesi (comparable in size to the living King Penguin), and the remains of three other previously undescribed penguin species, all of which seem to have preferred the tropics over colder latitudes. Perudyptes devriesi is named after the country, and Thomas DeVries, a University of Washington palaeontologist who has long worked in Peru. Standing 1.5 metres (5 ft) tall, the penguin was much larger than any of its modern-day cousins. It had an exceptionally long spear-like beak resembling that of a heron. The researchers who discovered the penguins believe the long, pointed beaks to be the likely ancestral shape for all penguins. Icadyptes salasi is the third largest penguin ever described. Icadyptes salasi and Perudyptes devriesi appear to have flourished at warmer latitudes at a time when world temperatures were at their warmest over the past 65 million years. Only a few modern-day penguins, such as the African and Galapagos penguins prefer such a balmy climate. The discovery of the fossils has caused a re-evaluation of penguin evolution and expansion. Previously, scientists believed that penguins evolved near the poles in Antarctica and New Zealand, and moved closer to the equator around 10 million years ago. Since Icadyptes salasi lived in Peru during a period of great warmth, penguins must have adapted to warm-climates around 30 million years earlier than previously believed.

- Palaeeudyptes (Middle/Late Eocene - Late Oligocene) - polyphyletic; some belong in other subfamilies : Palaeeudyptes is an extinct genus of large penguins, currently containing four accepted species. They were probably larger than almost all living penguins, with the smaller species being about the size of an Emperor Penguin and the largest ones having stood about 1.5 meters tall. Of the four species, two (P. gunnari and P. klekowskii) are known from numerous remains found in Middle or Late Eocene strata (34 to 50 MYA) of the La Meseta Formation on Seymour Island, Antarctica. P. antarcticus, the first fossil penguin described, is only really known from a single incomplete tarsometatarsus found in the Late Oligocene Otekaike Limestone (23 to 28, possibly up to 34 MYA) at Kakanui, New Zealand, but numerous other bones have been tentatively assigned to the species. The other described New Zealand species, P. marplesi, is known from parts of a skeleton, mainly leg bones, from the Middle or Late Eocene Burnside Mudstone (34 to 40 MYA) at Burnside, Dunedin. To this species also a number of additional remains have been tentatively assigned. The problem with the indeterminate New Zealand specimens is that they at least in part are intermediate in size between the two species (Simpson, 1971). It may be that P. marplesi simply evolved into the smaller P. antarcticus. Bones unassignable to species also were found on Seymour Island, but in these cases they seem to be from juvenile individuals or are simply too damaged to be of diagnostic value (Jadwiszczak, 2006). In addition, an incomplete right tibiotarsus (South Australian Museum P10862) and one left humerus (South Australian Museum P7158) and assignable to this genus were found in the Late Eocene Blanche Point Marls at Witton Bluff near Adelaide, Australia (Simpson, 1946, 1971). The supposed genus Wimanornis, based on two Seymour Island humeri, is apparently a synonym of P. gunnari (Jadwiszcak, 2006). The genus is the namesake for the subfamily of primitive penguins, Palaeeudyptinae. Altogether, their osteological characteristics seem to have been somewhat less advanced that those of the slightly smaller Archaeospheniscus and about on par with the gigantic Anthropornis. The exact nature of the relationship of the Palaeeudyptinae to modern penguins is unknown.

- Pachydyptes (Late Eocene) : Pachydyptes is an extinct genus of penguin. It contains the single species Pachydyptes ponderosus, the New Zealand Giant Penguin. This taxon is known from a few bones from Late Eocene (34 to 37 MYA) rocks in the area of Otago, and a fine specimen found near Kawhia, New Zealand, in January 2006[verification needed]. With a height of 140 to 160 cm (about 5 ft) and weighing around 80 to possibly over 100 kg, it was the second-tallest penguin ever, surpassed only by Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi in size, but probably not in weight. As George Gaylord Simpson famously quipped, "Pachydyptes' height would not suffice for basketball but their weight was about right for American football." Pachydyptes was slightly larger than Icadyptes salasi, the best-identified of the giant penguins.

- Anthropodyptes (Middle Miocene) - tentatively assigned to this subfamily : Anthropodyptes is a poorly known monotypic genus of extinct penguin. It contains the single species Anthropodyptes gilli, known from a Middle Miocene humerus from Australia. The bone is somewhat similar to those found in members of the New Zealand genus Archaeospheniscus and thus this genus might, like them, belong to the subfamily Palaeeudyptinae. [edit] References

- Subfamily Paraptenodytinae - Stout-legged penguins (fossil)

- Arthrodytes (San Julian Late Eocene/Early Oligocene - Patagonia Early Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina)

- Paraptenodytes (Early - Late Miocene/Early Pliocene) : Paraptenodytes is an extinct genus of penguins which contains two or three species sized between a Magellanic Penguin and a small Emperor Penguin (P. antarcticus). They are known from fossil bones ranging from a partial skeleton and some additional material in the case of P. antarcticus, and a single humerus in the case of P. brodkorbi. The latter species is therefore often considered invalid; Bertelli et al. (2006) think that it is indeed valid, but distinct enough not to belong into Paraptenodytes. The fossils were found in the Santa Cruz and Chubut Provinces of Patagonia, Argentina, in Patagonian Molasse Formation rocks of Early Miocene age; later occurrences are apparently from Late Miocene or possibly even Early Pliocene deposits (Stucchi et al. 2003). Together with the related genus Arthrodytes, they form the subfamily Paraptenodytinae, which is not an ancestor of modern penguins (Bertelli et al., 2006

- Subfamily Palaeospheniscinae - Slender-legged penguins (fossil) : Palaeospheniscus is an extinct genus of penguins which contains three species at present. They are all (except P. bergi, which is somewhat enigmatic) known from one or two handful of bones. All specimens were found in Santa Cruz and Chubut Provinces of Patagonia, Argentina. The fossils were recovered from the Patagonian Molasse Formation, and are probably Early Miocene to Late Miocene or possibly Early Pliocene in age (Stucchi et al. 2003). Palaeospheniscus gracilis was long believed to be from the Early Oligocene, but this is now thought to be erroneous. P. gracilis and P. wimani are often considered synonyms of P. patagonicus[citation needed]. Recent researchers also tend to merge Chubutodyptes into this genus as P. biloculatus[citation needed]. The species of Palaeospheniscus were medium-sized to largish penguins, ranging from P. gracilis with an estimated maximal length of 55 cm to P. wimani, which reached up to 73 cm. Palaeospheniscus is the namesake genus of the subfamily Palaeospheniscinae, the Patagonian slender-legged penguins. These are apparently not closely related to the modern genus Spheniscus.

- Eretiscus (Patagonia Early Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina)

- Palaeospheniscus (Early? - Late Miocene/Early Pliocene) - includes Chubutodyptes : Palaeospheniscus is an extinct genus of penguins which contains three species at present. They are all (except P. bergi, which is somewhat enigmatic) known from one or two handful of bones. All specimens were found in Santa Cruz and Chubut Provinces of Patagonia, Argentina. The fossils were recovered from the Patagonian Molasse Formation, and are probably Early Miocene to Late Miocene or possibly Early Pliocene in age (Stucchi et al. 2003). Palaeospheniscus gracilis was long believed to be from the Early Oligocene, but this is now thought to be erroneous. P. gracilis and P. wimani are often considered synonyms of P. patagonicus[citation needed]. Recent researchers also tend to merge Chubutodyptes into this genus as P. biloculatus[citation needed]. The species of Palaeospheniscus were medium-sized to largish penguins, ranging from P. gracilis with an estimated maximal length of 55 cm to P. wimani, which reached up to 73 cm. Palaeospheniscus is the namesake genus of the subfamily Palaeospheniscinae, the Patagonian slender-legged penguins. These are apparently not closely related to the modern genus Spheniscus.

- Subfamily Spheniscinae - Modern penguins

- Aptenodytes - Great penguins (2 species) : The genus Aptenodytes (from the Greek for "flightless diver") contains two extant species of penguins collectively known as "the great penguins".

Ridgen's Penguin (Aptenodytes ridgeni) is an extinct species known from fossil bones of Early or Late Pliocene age.

- Pygoscelis- Brush-tailed penguins (3 species)

- Eudyptula- Little penguins (2 species)

- Spheniscus- Banded penguins (4 species)

- Megadyptes- Yellow-eyed Penguin

- Eudyptes- Crested penguins (6-8 living species)

- Aptenodytes - Great penguins (2 species) : The genus Aptenodytes (from the Greek for "flightless diver") contains two extant species of penguins collectively known as "the great penguins".

- Subfamily Palaeeudyptinae - Giant penguins (fossil) : The New Zealand Giant Penguins, Palaeeudyptinae, are an extinct subfamily of penguins. It includes several genera of medium-sized to very large species - including Palaeeudyptes marplesi and Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi which grew 1.5 meters (4 ft 11.1 in) tall or even larger, and the massive Pachydyptes ponderosus which weighed at least as much as an adult human male. They belonged to an evolutionary lineage more primitive than modern penguins. In some taxa at least, the wing, while already having lost the avian feathering, had not yet transformed into the semi-rigid flipper found in modern penguin species: While the ulna and the radius were already flattened to increase propelling capacity, the elbow and wrist joints still retained a higher degree of flexibility than the more rigidly lockable structure found in modern genera. The decline and eventual disappearance of this subfamily seems to be connected by increased competition as mammal groups such as cetaceans and pinnipeds became better-adapted to a marine lifestyle in the Oligocene and Miocene. The members of this subfamily are known from fossils found in New Zealand, Antarctica, and possibly Australia, dating from the Middle or Late Eocene to the Late Oligocene; the Australian Middle Miocene genus Anthropodyptes is also often assigned to this subfamily, as are the remaining genera of primitive penguins except those from Patagonia. Indeed, it was long assumed that all prehistoric penguins which cannot be assigned to extant genera belonged into the Palaeeudyptinae; this view is generally considered obsolete today. It is likely that some of the unassigned New Zealand/ Antarctican/ Australian genera like Delphinornis, Marambiornis, and Mesetaornis do indeed belong into this subfamily, but it is just as probable that others, such as Duntroonornis and Korora, represent another, smaller and possibly somewhat more advanced lineage. The Palaeeudyptinae as originally defined (Simpson, 1946) contained only the namesake genus, the remainder being placed in the Anthropornithidae. The arrangement followed here is based on the review of Marples (1962) who synonymized the two, with updates to incorporate more current findings.

Taxonomy: Clarke et al. (2003) and Ksepka et al. (2006) apply the phylogenetic taxon Spheniscidae what here is referred to as Spheniscinae. Furthermore, they restrict the phylogenetic taxon Sphenisciformes to flightless taxa, and establish (Clarke et al. 2003) the phylogenetic taxon Pansphenisciformes as equivalent to the Linnean taxon Sphenisciformes, i.e., including any flying basal "proto-penguins" to be discovered eventually. Given that neither the relationships of the penguin subfamilies to each other nor the placement of the penguins in the avian phylogeny is presently resolved, this seems spurious and in any case is confusing; the established Linnean system is thus followed here.

Evolution

The evolutionary history of penguins is well-researched and represents a showcase of evolutionary biogeography; though as penguin bones of any one species vary much in size and few good specimens are known, the alpha taxonomy of many prehistoric forms still leaves much to be desired. Some seminal articles about penguin prehistory have been published since 2005 (Bertelli & Giannini 2005, Baker et al. 2006, Ksepka et al. 2006, Slack et al. 2006), the evolution of the living genera can be considered resolved by now.

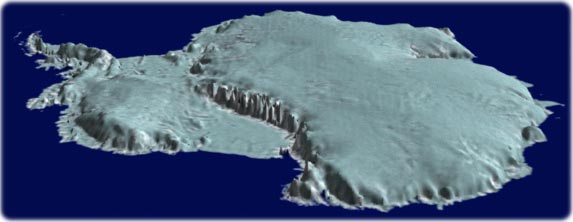

According to the comprehensive review of the available evidence by Ksepka et al. (2006), the basal penguins lived around the time of the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event somewhere in the general area of (southern) New Zealand and Byrd Land, Antarctica. Due to plate tectonics, these areas were at that time less than 1,500 kilometers (932 mi) apart rather than the 4,000 kilometers (2,486 mi) of today. The most recent common ancestor of penguins and their sister clade can be roughly dated to the Campanian-Maastrichtian boundary, around 70-68 mya (Baker et al. 2006, Slack et al. 2006). What can be said as certainly as possible in the absence of direct (i.e., fossil) evidence is that by the end of the Cretaceous, the penguin lineage must have been evolutionarily well distinct, though much less so morphologically; it is fairly likely that they were not yet entirely flightless at that time, as flightless birds have generally low resilience to the breakdown of trophic webs which follows the initial phase of mass extinctions because of their below-average dispersal capabilities (see also Flightless Cormorant).

Origin and systematics of modern penguins

Modern penguins constitute two undisputed clades and another two more basal genera with more ambiguous relationships (Bertelli & Giannini 2005). The origin of the Spheniscinae lies probably in the latest Paleogene, and geographically it must have been much the same as the general area in which the order evolved: the oceans between the Australia-New Zealand region and the Antarctic (Baker et al. 2006). Presumedly diverging from other penguins around 40 mya (Baker et al. 2006), it seems that the Spheniscinae were for quite some time limited to their ancestral area, as the well-researched deposits of the Antarctic Peninsula and Patagonia have not yielded Paleogene fossils of the subfamily. Also, the earliest spheniscine lineages are those with the most southern distribution.

The genus Aptenodytes appears to be the basalmost divergence among living penguins; they have bright yellow-orange neck, breast, and bill patches, incubate by placing their eggs on their feet, and when they hatch, they are almost naked. This genus has a distribution centered on the Antarctic coasts and barely extends to some subantarctic islands today.

Pygoscelis contains species with a fairly simple black-and-white head pattern; their distribution is intermediate, centered on Antarctic coasts but extending somewhat northwards from there. In external morphology, these apparently still resemble the common ancestor of the Spheniscinae, as Aptenodytes' autapomorphies are in most cases fairly pronounced adaptations related to that genus' extreme habitat conditions. As the former genus, Pygoscelis seems to have diverged during the Bartonian, but the range expansion and radiation which lead to the present-day diversity probably did not occur until much later, around the Burdigalian stage of the Early Miocene, roughly 20-15 mya (Baker et al. 2006).

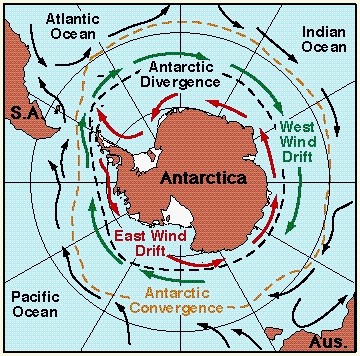

The genera Spheniscus and Eudyptula contain species with a mostly subantarctic distribution centered on South America; some, however, range quite far northwards. They all lack carotenoid coloration, and the former genus has a conspicuous banded head pattern; they are unique among living penguins in nesting in burrows. This group probably radiated eastwards with the Antarctic Circumpolar Current out of the ancestral range of modern penguins throughout the Chattian (Late Oligocene), starting approximately 28 mya (Baker et al. 2006). While the two genera separated during this time, the present-day diversity is the result of a Pliocene radiation, taking place some 4-2 mya (Baker et al. 2006).

The Megadyptes -Eudyptes clade occurs at similar latitudes (though not as far north as the Galapagos Penguin), has its highest diversity in the New Zealand region, and represent a westward dispersal. They are characterized by hairy yellow ornamental head feathers; their bills are at least partly red. These two genera diverged apparently in the Middle Miocene (Langhian, roughly 15-14 mya), but again, the living species of Eudyptes are the product of a later radiation, stretching from about the late Tortonian (Late Miocene, 8 mya) to the end of the Pliocene (Baker et al. 2006).

It is most interesting to note that the geographical and temporal pattern or spheniscine evolution corresponds closely to two episodes of global cooling documented in the paleoclimatic record (Baker et al. 2006). The emergence of the subantarctic lineage at the end of the Bartonian corresponds with the onset of the slow period of cooling that eventually led to the ice ages some 35 million years later. With habitat on the Antarctic coasts declining, by the Priabonian more hospitable conditions for most penguins existed in the subantarctic regions rather than in Antarctica itself. Notably, the cold Antarctic Circumpolar Current also started as a continuous circumpolar flow only around 30 mya, on the one hand forcing the Antarctic cooling, and on the other facilitating the eastward expansion of Spheniscus to South America and eventually beyond (Baker et al. 2006).

Later, an interspersed period of slight warming was ended by the Middle Miocene Climate Transition, a sharp drop in global average temperature from 14 to 12 mya, and similar abrupt cooling events followed at 8 mya and 4 mya; by the end of the Tortonian, the Antarctic ice sheet was already much like today in volume and extent. The emergence of most of today's subantarctic penguin species almost certainly was caused by this sequence of Neogene climate shifts.

Relationship to other bird orders

Penguin ancestry beyond Waimanu remains unknown and not well resolved by molecular or morphological analyses. The latter tend to be confounded by the strong adaptive autapomorphies of the Sphenisciformes; a sometimes perceived fairly close relationship between penguins and grebes is almost certainly an error based on both groups' strong diving adaptations, which are homoplasies. On the other hand, different DNA sequence datasets do not agree in detail with each other either.

What seems clear is that penguins belong to a clade of Neoaves (living birds except paleognaths and fowl) which comprises what is sometimes called "higher waterbirds" to distinguish them from the more ancient waterfowl. This group contains such birds as storks, rails, and the seabirds, with the possible exception of the Charadriiformes (Fain & Houde 2004).

Inside this group, penguin relationships are far less clear. Depending on the analysis and dataset, a close relationship to Ciconiiformes (e.g. Slack et al. 2006) or to Procellariiformes (Baker et al. 2006) has been suggested. Some (e.g. Mayr 2005) think the penguin-like plotopterids (usually considered relatives of anhingas and cormorants) may actually be a sister group of the penguins, and that penguins may have ultimately shared a common ancestor with the Pelecaniformes and consequently would have to be included in that order, or that the plotopterids were not as close to other pelecaniforms as generally assumed, which would necessitate splitting the traditional Pelecaniformes in three.

The Auk of the Northern Hemisphere is superficially similar to penguins, they are not related to the penguins at all, but considered by some to be a product of moderate convergent evolution.

Copyright: Wikipedia. This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from Wikipedia.org

No comments:

Post a Comment