Emperor penguins maintain the tight huddle that protects them from

the harsh conditions of an Antarctic winter with stop-and-go movements

like cars in a traffic jam, a new study has shown. (Credit: Daniel

Zitterbart)

Emperor penguins maintain the tight huddle that protects them from

the harsh conditions of an Antarctic winter with stop-and-go movements

like cars in a traffic jam, a new study has shown. (Credit: Daniel

Zitterbart)

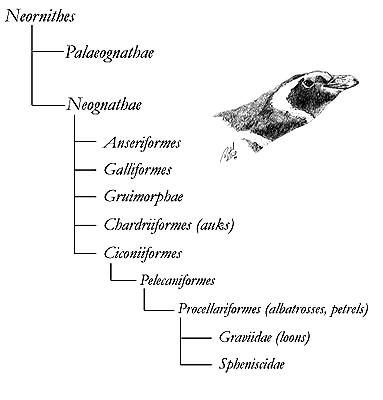

Dec. 16, 2013 — Emperor

penguins maintain the tight huddle that protects them from the harsh

conditions of an Antarctic winter with stop-and-go movements like cars

in a traffic jam, a new study has shown.

By using a mathematical model that recreated the positions, movements

and interactions of individual penguins in a huddle, researchers have

revealed that an individual penguin only needs to move 2 cm in any

direction for its neighbour to react and also perform a step to stay

close to it.

These movements then flow through the entire huddle like a travelling

wave and play a vital role in keeping the huddle as dense as possible

to protect the penguins from the cold; the wave also helps smaller

huddles merge into larger ones.

The results have been published today, 17 December, in the Institute of Physics and German Physical Society's New Journal of Physics and are accompanied by a video abstract. An advanced set of videos can be viewed here -- http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLx-sGUtkV82eZJHWNyJ4uxPCBtb1GlWgw

In a previous study, the same group of researchers studied time-lapse videos and showed that instead of remaining static, penguins in a huddle actually move every 30-60 seconds, causing surrounding penguins to move with them.

Co-author of the study Daniel Zitterbart, from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), said: "Our previous study showed how penguins use travelling waves to allow movement in a densely packed huddle, but we had no explanation as to how these waves propagate and how they are triggered."

To investigate this, the researchers used a mathematical model, which has previously been used to study traffic jams, and compared the results with an analysis of video recordings of a real-life penguin huddle.

Unlike a traffic jam, the researchers found that the waves of movements in a penguin huddle can originate from any single penguin and can propagate in any direction as soon as a sufficient gap, known as a "threshold distance," develops between two penguins.

This threshold distance was estimated to be around 2 cm, which is twice the thickness of a penguin's compressive feather layer, suggesting the penguins touch each other only slightly when standing in a huddle without compressing the feather layer so as to maximize huddle density without compromising their own insulation.

"We were really surprised that a travelling wave can be triggered by any penguin in a huddle, rather than penguins on the outside trying to push in," continued Zitterbart. "We also found it amazing how two waves, if triggered shortly after each other, merged instead of passing one another, making sure the huddle remains compact."

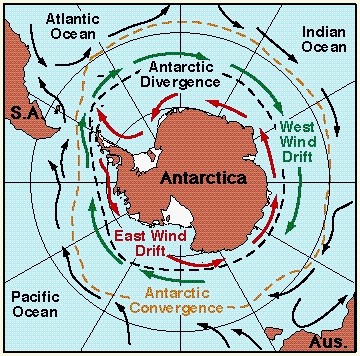

The emperor penguin is the only vertebrate species that breeds during the severe conditions of the Antarctic winter. At this time of year temperatures can get as low as -50°C and winds can reach speeds of up to 200 km/h.

To cope with the harsh conditions, the male penguins form dense huddles, often consisting of thousands of individuals, to maintain their body temperatures. Unlike other species of penguin, the male emperors are solely responsible for incubating their single egg during the winter, covering it in an abdominal pouch above their feet while the female returns to sea to feed.

The results have been published today, 17 December, in the Institute of Physics and German Physical Society's New Journal of Physics and are accompanied by a video abstract. An advanced set of videos can be viewed here -- http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLx-sGUtkV82eZJHWNyJ4uxPCBtb1GlWgw

In a previous study, the same group of researchers studied time-lapse videos and showed that instead of remaining static, penguins in a huddle actually move every 30-60 seconds, causing surrounding penguins to move with them.

Co-author of the study Daniel Zitterbart, from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), said: "Our previous study showed how penguins use travelling waves to allow movement in a densely packed huddle, but we had no explanation as to how these waves propagate and how they are triggered."

To investigate this, the researchers used a mathematical model, which has previously been used to study traffic jams, and compared the results with an analysis of video recordings of a real-life penguin huddle.

Unlike a traffic jam, the researchers found that the waves of movements in a penguin huddle can originate from any single penguin and can propagate in any direction as soon as a sufficient gap, known as a "threshold distance," develops between two penguins.

This threshold distance was estimated to be around 2 cm, which is twice the thickness of a penguin's compressive feather layer, suggesting the penguins touch each other only slightly when standing in a huddle without compressing the feather layer so as to maximize huddle density without compromising their own insulation.

"We were really surprised that a travelling wave can be triggered by any penguin in a huddle, rather than penguins on the outside trying to push in," continued Zitterbart. "We also found it amazing how two waves, if triggered shortly after each other, merged instead of passing one another, making sure the huddle remains compact."

The emperor penguin is the only vertebrate species that breeds during the severe conditions of the Antarctic winter. At this time of year temperatures can get as low as -50°C and winds can reach speeds of up to 200 km/h.

To cope with the harsh conditions, the male penguins form dense huddles, often consisting of thousands of individuals, to maintain their body temperatures. Unlike other species of penguin, the male emperors are solely responsible for incubating their single egg during the winter, covering it in an abdominal pouch above their feet while the female returns to sea to feed.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Institute of Physics, via EurekAlert!, a service of AAAS.

Note: Materials may be edited for content and length. For further information, please contact the source cited above.

Journal Reference:

- R C Gerum, B Fabry, C Metzner, M Beaulieu, A Ancel, D P Zitterbart. The origin of traveling waves in an emperor penguin huddle. New Journal of Physics, 2013; 15 (12): 125022 DOI: 10.1088/1367-2630/15/12/125022

Institute of Physics (2013, December 16). Traffic jams lend insight into emperor penguin huddle. ScienceDaily. Retrieved December 17, 2013, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2013/12/131216204020.htm