- Date:

- February 23, 2017

- Source:

- Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum

- Summary:

- A recently discovered fossil of a giant penguin with a body length of around 150 centimeters has been described in a new article. The new find dates back to the Paleocene era and, with an age of approximately 61 million years, counts among the oldest penguin fossils in the world. The bones differ significantly from those of other discoveries of the same age and indicate that the diversity of Paleocene penguins was higher than previously assumed. The team of scientists, therefore postulates that the evolution of penguins started much earlier than previously thought, probably already during the age of dinosaurs.

The foot bones of the new giant penguin (left), compared to those of an Emperor Penguin, the largest living penguin species (right).

Credit: © Senckenberg

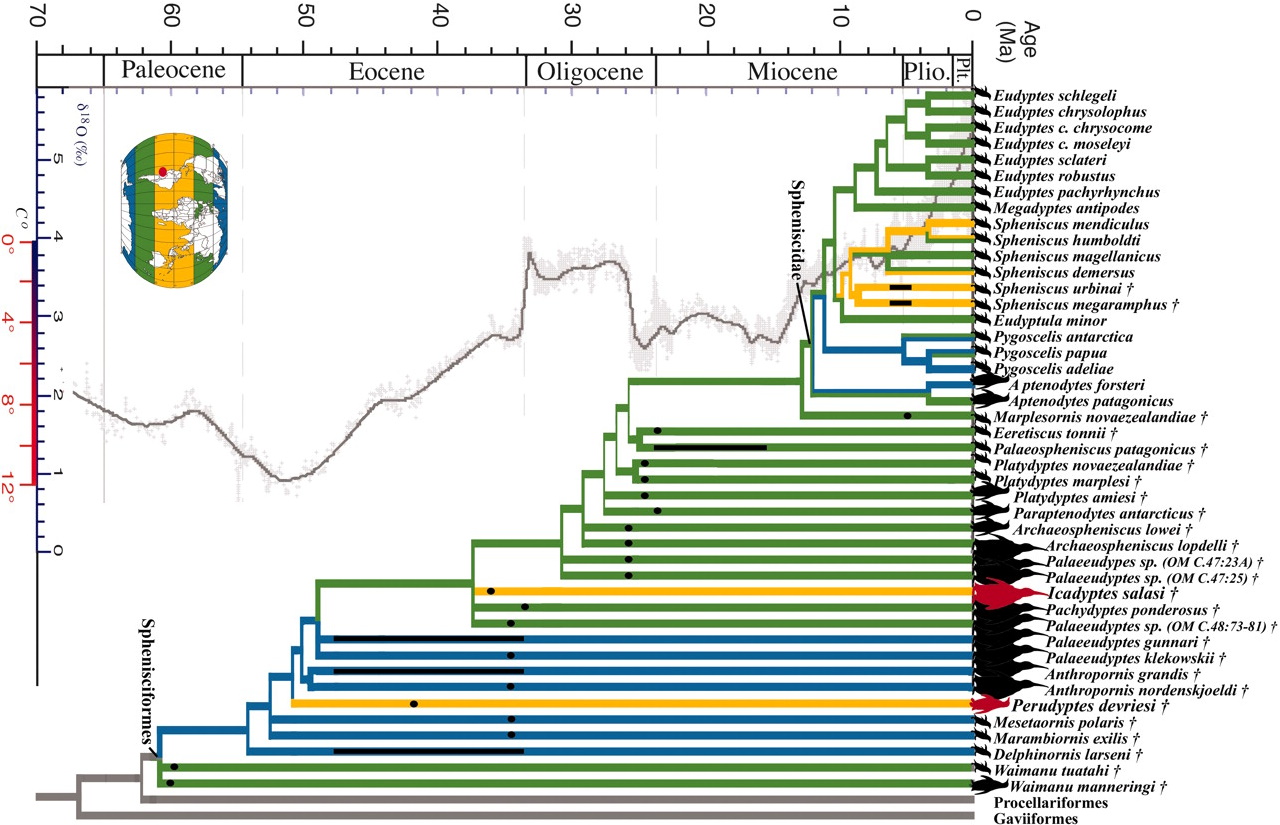

Together with colleagues from New Zealand, Senckenberg scientist Dr. Gerald Mayr described a recently discovered fossil of a giant penguin with a body length of around 150 centimeters. The new find dates back to the Paleocene era and, with an age of approx. 61 million years, counts among the oldest penguin fossils in the world. The bones differ significantly from those of other discoveries of the same age and indicate that the diversity of Paleocene penguins was higher than previously assumed. In their study, published in the Springer scientific journal The Science of Nature, the team of scientists, therefore postulates that the evolution of penguins started much earlier than previously thought, probably already during the age of dinosaurs.

The fossil sites along the Waipara River in New Zealand's Canterbury region are well known for their avian fossils, which were embedded in marine sand a mere 4 million years after the dinosaurs became extinct. "Among the finds from these sites, the skeletons of Waimanu, the oldest known penguin to date, are of particular importance," explains Dr. Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt.

Together with colleagues from the Canterbury Museum in New Zealand, Mayr now described a newly discovered penguin fossil from the famous fossil site. "What sets this fossil apart are the obvious differences compared to the previously known penguin remains from this period of geological history," explains the ornithologist from Frankfurt, and he continues, "The leg bones we examined show that during its lifetime, the newly described penguin was significantly larger than its already described relatives. Moreover, it belongs to a species that is more closely related to penguins from later time periods."

According to the researchers, the newly described penguin lived about 61 million years ago and reached a body length of approx. 150 centimeters -- making it almost as big as Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi, the largest known fossil penguin, which lived in Antarctica around 45 to 33 million years ago, thus being much younger in geological terms. "This shows that penguins reached an enormous size quite early in their evolutionary history, around 60 million years ago," adds Mayr.

In addition, the team of scientists from New Zealand and Germany assumes that the newly discovered penguin species also differed from their more primitive relatives in the genus Waimanu in their mode of locomotion: The large penguins presumably already moved with the upright, waddling gait characteristic for today's penguins.

"The discoveries show that penguin diversity in the early Paleocene was clearly higher than we previously assumed," says Mayr, and he adds, "In turn, this diversity indicates that the first representatives of penguins already arose during the age of dinosaurs, more than 65 million years ago."

Together with colleagues from the Canterbury Museum in New Zealand, Mayr now described a newly discovered penguin fossil from the famous fossil site. "What sets this fossil apart are the obvious differences compared to the previously known penguin remains from this period of geological history," explains the ornithologist from Frankfurt, and he continues, "The leg bones we examined show that during its lifetime, the newly described penguin was significantly larger than its already described relatives. Moreover, it belongs to a species that is more closely related to penguins from later time periods."

According to the researchers, the newly described penguin lived about 61 million years ago and reached a body length of approx. 150 centimeters -- making it almost as big as Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi, the largest known fossil penguin, which lived in Antarctica around 45 to 33 million years ago, thus being much younger in geological terms. "This shows that penguins reached an enormous size quite early in their evolutionary history, around 60 million years ago," adds Mayr.

In addition, the team of scientists from New Zealand and Germany assumes that the newly discovered penguin species also differed from their more primitive relatives in the genus Waimanu in their mode of locomotion: The large penguins presumably already moved with the upright, waddling gait characteristic for today's penguins.

"The discoveries show that penguin diversity in the early Paleocene was clearly higher than we previously assumed," says Mayr, and he adds, "In turn, this diversity indicates that the first representatives of penguins already arose during the age of dinosaurs, more than 65 million years ago."

Story Source:

Materials provided by Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Materials provided by Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Gerald Mayr, Vanesa L. De Pietri, R. Paul Scofield. A new fossil from the mid-Paleocene of New Zealand reveals an unexpected diversity of world’s oldest penguins. The Science of Nature, 2017; 104 (3-4) DOI: 10.1007/s00114-017-1441-0

Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum. "The oldest fossilized giant penguin: Penguins diversified earlier than previously assumed." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 23 February 2017. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/02/170223102022.htm>.