Date:

May 22, 2015

- Source:

- Taylor & Francis

- Summary:

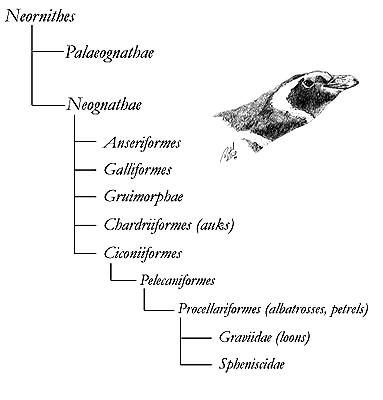

- A new study of some primitive birds from the Cretaceous shows how several separate lineages evolved adaptations for diving. Living at the same time as the dinosaurs, Hesperornithiform bird fossils have been found in North America, Europe and Asia in rocks 65-95 million years old. This research shows that separate lineages became progressively more adept at diving into water to catch fishes, like modern day loons and grebes.

Evolution of diving specializations within the Hesperornithiformes. Credit: Image courtesy of Taylor & Francis

Evolution of diving specializations within the Hesperornithiformes. Credit: Image courtesy of Taylor & Francis

A new study of some primitive birds from the Cretaceous shows how several separate lineages evolved adaptations for diving.

Living at the same time as the dinosaurs, Hesperornithiform bird

fossils have been found in North America, Europe and Asia in rocks 65-95

million years old. Dr Alyssa Bell and Professor Luis Chiappe of the

Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County,

publishing in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, have

undertaken a detailed analysis of their evolution, showing that separate

lineages became progressively more adept at diving into water to catch

fishes, like modern day loons and grebes.

The Hesperornithiformes are a highly derived but very understudied group of primitive birds from the Cretaceous period. This study is the first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis, or evaluation of evolutionary relationships, to ever be undertaken on the entire group.

The results of this study confirm that the Hesperornithiformes do form a single group (or clade), but that within this group the inter-relationships of the different taxa are more complex than previously thought. Additionally, this study finds that anatomical changes were accompanied by enlargement in overall body size, which increased lung capacity and allowed deeper diving.

Overall, this study provides evidence for understanding the evolution of diving adaptations among the earliest known aquatic birds.

The Hesperornithiformes are a highly derived but very understudied group of primitive birds from the Cretaceous period. This study is the first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis, or evaluation of evolutionary relationships, to ever be undertaken on the entire group.

The results of this study confirm that the Hesperornithiformes do form a single group (or clade), but that within this group the inter-relationships of the different taxa are more complex than previously thought. Additionally, this study finds that anatomical changes were accompanied by enlargement in overall body size, which increased lung capacity and allowed deeper diving.

Overall, this study provides evidence for understanding the evolution of diving adaptations among the earliest known aquatic birds.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Taylor & Francis. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

The above story is based on materials provided by Taylor & Francis. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

- Alyssa Bell, Luis M. Chiappe. A species-level phylogeny of the Cretaceous Hesperornithiformes (Aves: Ornithuromorpha): implications for body size evolution amongst the earliest diving birds. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2015; 1 DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2015.1036141

Taylor

& Francis. "Go fish! Ancient birds evolved specialist diving

adaptations." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 22 May 2015.

<www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/05/150522105222.htm>.