Authors:

- Published: April 23, 2014

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095375

Abstract

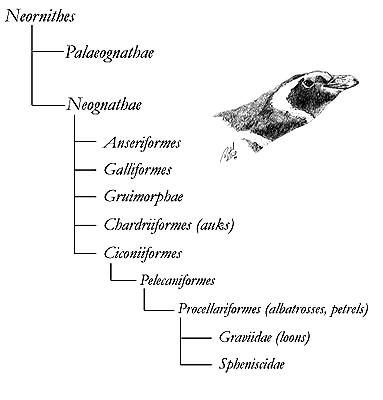

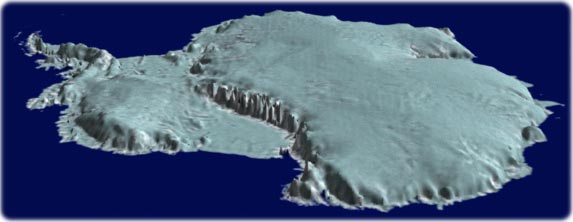

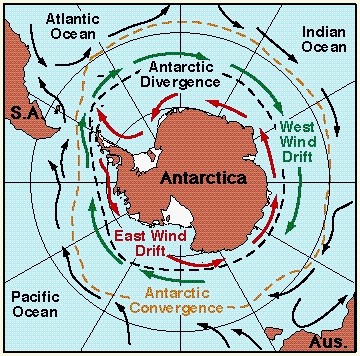

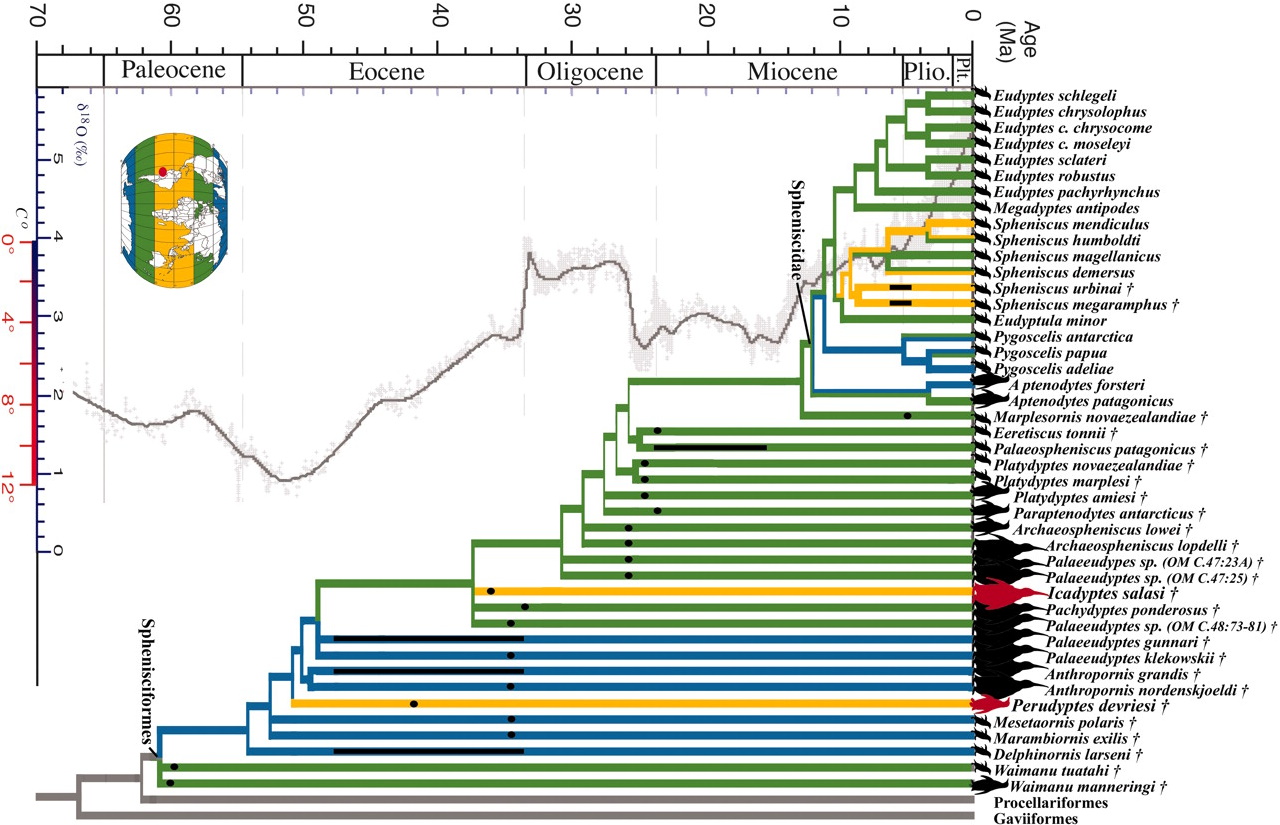

The West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) has been suffering an increase in its atmospheric temperature during the last 50 years, mainly associated with global warming. This increment of temperature trend associated with changes in sea-ice dynamics has an impact on organisms, affecting their phenology, physiology and distribution range. For instance, rapid demographic changes in Pygoscelis penguins have been reported over the last 50 years in WAP, resulting in population expansion of sub-Antarctic Gentoo penguin (P. papua) and retreat of Antarctic Adelie penguin (P. adeliae). Current global warming has been mainly associated with human activities; however these climate trends are framed in a historical context of climate changes, particularly during the Pleistocene, characterized by an alternation between glacial and interglacial periods. During the last maximal glacial (LGM~21,000 BP) the ice sheet cover reached its maximum extension on the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP), causing local extinction of Antarctic taxa, migration to lower latitudes and/or survival in glacial refugia. We studied the HRVI of mtDNA and the nuclear intron βfibint7 of 150 individuals of the WAP to understand the demographic history and population structure of P. papua. We found high genetic diversity, reduced population genetic structure and a signature of population expansion estimated around 13,000 BP, much before the first paleocolony fossil records (~1,100 BP). Our results suggest that the species may have survived in peri-Antarctic refugia such as South Georgia and North Sandwich islands and recolonized the Antarctic Peninsula and South Shetland Islands after the ice sheet retreat.Click this link to download the full paper

Satellite-based penguin monitoring enables researchers to uncover how the species reacts to the climate change [Credit: Alasdair]

Satellite-based penguin monitoring enables researchers to uncover how the species reacts to the climate change [Credit: Alasdair] The unobtrusive cameras rely on car batteries to survive Antarctic winter and a Raspberry Pi computer to communicate with

The unobtrusive cameras rely on car batteries to survive Antarctic winter and a Raspberry Pi computer to communicate with