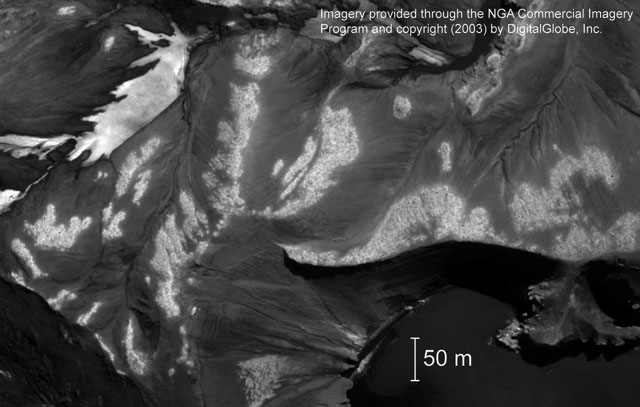

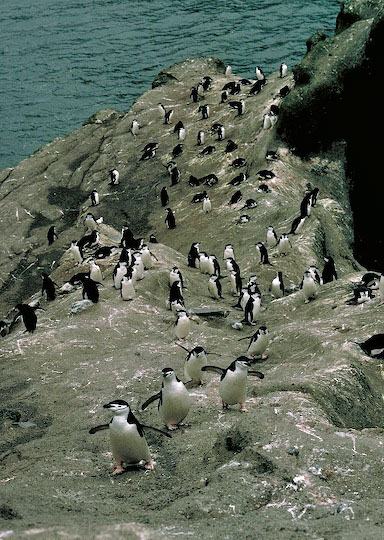

Photo Credit: ©Ron Naveen/Oceanites Inc. |

Chinstrap penguins at

Baily Head, Deception Island, off the Antarctic Peninsula. Researchers

have documented at least a 50 percent decline in the population over the

last 20 years. Various factors may be involved, but scientists don't

believe tourism is a contributing factor. |

By Peter Rejcek, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted September 7, 2012

An iconic chinstrap penguin colony on Deception Island, a

popular stop for tourists to the Antarctic Peninsula, has declined by

more than 50 percent in the last 25 years.

That’s the conclusion published last month in the journal

Polar Biology

by a team of researchers that spent 12 days in December 2011 counting

individual penguin nests on the remote Antarctic island. The census

found nearly 80,000 breeding pairs, with about 50,000 at a location

called Baily Head.

The results were compared against a 1986-87 survey,

refined with a simulation designed to capture uncertainty in the earlier

population estimate by

British Antarctic Survey (BAS)

scientists.

It had already been known that the colony was in steady

decline but no one had been able to quantify the plummet in population

until now.

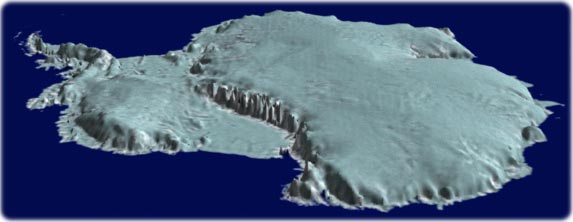

Photo Credit: ©Ron Naveen/Oceanites Inc.

An aerial view of chinstrap penguin colony at Baily Head, Deception Island.

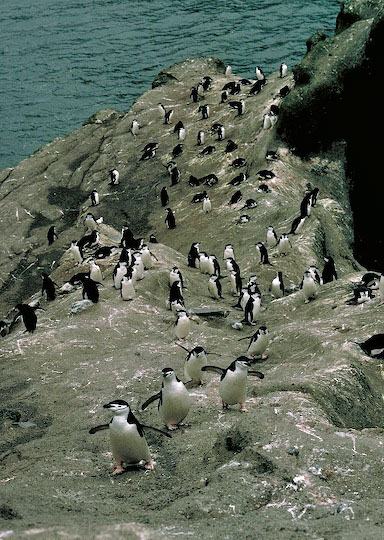

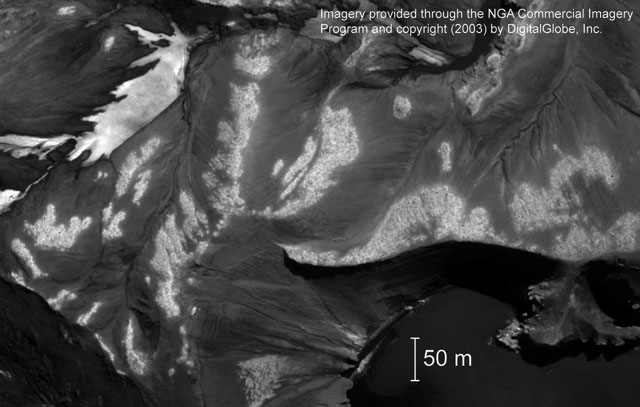

Photo Credit: ©DigitalGlobe Inc.; Image provided by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Commercial Imagery Program

A satellite image shows chinstrap penguin colonies at Baily Head, Deception Island, in 2003.

“It was really nice to be able to put a number on the

decline, since so many people were tossing around estimates that were

not based in data,” said

Heather Lynch

, an assistant professor at

Stony Brook University

and co-author on the paper. “Now we at least know exactly the status of

Deception, which is important both scientifically and for tourism.”

There has been concern by nations party to the

Antarctic Treaty System

that the population crash at Baily Head was due largely to tourism.

During the 2010-11 season, 1,354 tourists visited Baily Head, a massive

amphitheater of breeding chinstrap penguins on the island’s eastern

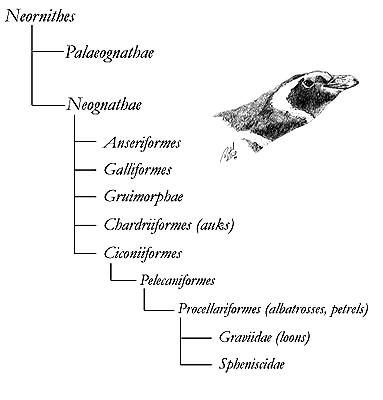

shore. The common name for

Pygoscelis antarctica comes from the thin black line that runs around the penguin’s head.

However, the drop in the chinstrap population at Baily

Head is consistent with population declines of the species at other

locations, including sites that receive little or no tourism, according

to Ron Naveen, founder of

Oceanites Inc.

,

a nonprofit organization that since 1994 has conducted the Antarctic

Site Inventory, an ongoing census of the seabird populations around the

Antarctic Peninsula.

Previously, the researchers had published results from

surveys of 29 chinstrap colonies that found significant declines at 16

sites and increases at only seven. Another one of the so-called

brushtailed penguins, Adélie numbers are also crashing along the

northwestern Antarctic Peninsula. The third brushtailed species,

gentoos, appears to be increasing in numbers. [See previous story —

The big picture: Broad-scale study suggests sea ice not driving changes in penguin populations.]

Pressures from climate change are believed to be hurting

the Adélie and chinstrap colonies off the Antarctic Peninsula, where

temperatures have increased by about 3 degrees Celsius in the summer and

almost double that in the winter. In particular, the Adélies rely on

sea ice as a key habitat. And while subantarctic chinstraps aren’t as

reliant on the seasonal pack ice, which is also shrinking in duration

and extent, food sources such as krill graze on the algae that grow

under the ice. Other factors may also be in play.

The team backed up its census data with a comparison of

satellite imagery between the 2002-2003 and 2009-2010 summer seasons.

During that seven-year period, the chinstrap population dropped by an

estimated 39 percent, though there was a larger degree of uncertainty

because of the difficulty involved in estimating nest density from the

satellite imagery.

Photo Credit: ©Ron Naveen/Oceanites Inc.

A chinstrap penguin at Baily Head, Deception Island.

Photo Credit: ©Ron Naveen/Oceanites Inc.

Chinstrap penguin breeding pair with chick at Baily Head, Deception Island.

Photo Credit: ©Ron Naveen/Oceanites Inc.

Chinstrap penguins return to their nests from the small cove on the southwestern side of Baily Head, Deception Island.

“We do not yet have very sophisticated models for nesting

density, but we are working on them, and these will fit nicely into

everything we have developed to date and will allow us to shrink those

error bars substantially,” Lynch said.

Despite the uncertainty, there was a remarkable

correspondence between the field census and the satellite image counts,

according to Lynch.

“The two census estimates were completed entirely

independently using separate ‘pools’ of information,” she explained. “We

were completely shocked at how close the two census estimates were to

one another. I think this is a really incredible validation that the

high-resolution satellite imagery can produce census data of the same

quality as can be obtained in the field and, potentially, over a much

larger scale.”

Lynch is a proponent of remote-sensing conservation, a

growing field that uses satellite imagery to monitor wildlife

populations. The technique has been used in the Antarctic to assess seal

populations as well as penguin colonies. [See previous story —

Eyes in the sky: Scientists use satellites to track health of seal, penguin populations in Antarctica.] She is also an advisory member of the

Polar Geospatial Center (PGC)

, based at the

University of Minnesota

. PGC has access, through the

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

, to high-resolution commercial satellite imagery.

Fortunately, for seasoned and enthusiastic field hands

like Naveen, there’s still a need to visit and census the animals on the

ground.

“The reason that we were able to use the satellite

imagery so successfully is because we have a lot of ground truthing data

— density estimates, photo-documentation, personal experience — and as

we start expanding this approach, our investment in regional-scale

census work is going to pay major dividends,” Lynch said.

Of course, the fieldwork isn’t as romantic as it sounds.

The 12-day stint on Deception Island was as much a function of nasty

weather — persistent clouds, precipitation and at times gale-force winds

— as the desire to fill in a key gap in the Oceanites dataset,

according to Naveen.

“Deception [has] never been fully censused in one season,

let alone 12 days. Unfortunately, the weather was such that we never

left Deception,” he said. “I wanted to make sure we had those data in

hand and this coming season we’ll be doing more ‘gap’-filling work.”

In 18 years, Oceanites teams have conducted more than

1,200 census visits at 169 locations over an area covering more than

100,000 square kilometers. Naveen said he is eager to continue the

census work, especially with the more sophisticated analytical tools

employed by Lynch and her lab.

“Assessing and analyzing the changes now occurring in the

peninsula is an engrossing and thoroughly complex undertaking,” he

said. “The statistics and photo-analytical resources we have available,

and the new ones that we’re developing, particularly in regard to using

satellite photo-documentation … will give all of us a better

understanding of what’s driving change in the vastly warming peninsula

ecosystem.”

source